If the construction sector is to become sustainable, urban mining is key. But how do we mine our buildings, if we don’t know what they’re made of in the first place? That’s where a materials passport comes in.

Just as a regular passport provides personal details of someone’s identity, the equivalent document for materials provides insight into the identity of a building. Typically in the form of digital data sets, these records of exactly what materials, products, and components go into a structure make it vastly easier at the end of the building’s life to recover everything of value, preventing these materials from being dumped or incinerated during demolition or renovation.

As Dutch architect Thomas Rau says: “waste is material without an identity”. It is a vision he has put into practice as one of the founders of Madaster, who operate an online library of materials linked to their location. This platform allows stakeholders along the construction chain to upload data on the products and components in a building, and automatically generates a material passport.

Materials passports can reduce environmental impacts

By 2060, the land area of built property on the planet is expected to double. This would mean an additional 230 billion square metres in new construction, or the equivalent of building the current floor area of Japan every single year until 2060.

These buildings will require large amounts of material and energy to produce. Globally the construction sector accounts for 6% of global energy use and nearly 11% of energy-related CO2 emissions. In the Netherlands, it is responsible for 50% of all waste produced. Although some construction material is recycled at the end of its life, most of it is downcycled: crushed and made into low-value rubble, often used as a foundational layer underneath new infrastructure projects or as unpaved roads.

If we can find a way to reuse building materials for new construction without breaking them down and decreasing their value,the energy, labour, and transportation costs of producing new materials can be saved, and so can the associated emissions. That’s where materials passports can help.

What do materials passports look like?

The overall goal of a materials passport is to document materials present in a product or building to maximize reuse potential. Different types of material passports have been developed, with varying approaches. The actual document can be anything that includes this information: from an excel sheet to a detailed 3D model of a building, or a distributed blockchain-based ledger that secures the information. A materials passport can be an online platform that interacts with an SQL database, or it can even be a book with a pen-and-paper record of materials, impacts and supply chains.

What these documents have in common is that, like a nutritional label on a food jar in the supermarket, they provide information on the building in question. Unlike a food label, however, a materials passport needs to hold a lot more information than just the building’s ‘ingredients’.. Ideally, it should also show what materials make up its components, and the journey they have been on: where they originated, who supplied them, their current condition after construction and wear and tear, real-time market price, and associated environmental impact.

If this sounds like a lot of information, it is. As the data becomes more complex, passport documents are also starting to accommodate more and more of it. Complexity is one of the key challenges of materials passports, but it also presents a unique opportunity. This level of detail allows owners and municipalities to have an increasingly sophisticated understanding of what is inside a building, and its economic, social, and environmental value.

Calculating value

Materials passports can cover everything from the foundations of a building, to the front facade, window frames, inner walls, and right up to the ceiling and roof structure. They can also detail the materials used in public spaces and infrastructure such as roads and bridges.

Beyond identifying what components are being used, a materials passport also allows for a better idea of the value of a particular building. Just as there are precise valuations of the space and location, a breakdown of the materials means it is easier to calculate the specific value of a building’s material worth. And this can add up: for instance, a study for the Metropolitan Region of Amsterdam calculated that the 2.6 million tonnes of building materials released each year through renovation and demolition in Amsterdam has a value of €688 million.

The theory of materials passports is already being put into action: the project Buildings As Material Banks (BAMB), an EU-backed collaboration between 15 partners from 7 European countries, undertook a range of pilot projects, including a new office building in Essen, Germany, using Material Passports to build to Cradle-to-Cradle principles.

Informing circular design

Of course, simply recording what ingredients make up a building does not guarantee that those materials can be reused. In addition to specifying the materials that go into a building, a materials passport can also provide insight into how sustainable, recyclable, healthy, and safe they are. These documents can be powerful tools to encourage the re-use of components and recycling of materials, as well as encouraging the use of materials which are environmentally-friendly and not over-exploited. If construction is being planned with circularity and sustainability goals in mind, a materials passport can serve as a prompt at the design phase to ensure that buildings are using components that can be easily and safely reused, such as Cradle-to-Cradle Certified Products like Daas ClickBrick facades: self-gripping bricks which install with fasteners rather than chemical connections, which allow for easy disassembly and reuse. Another example is Shaw Ecoworx carpet tiles, which are free of harmful chemicals to allow for recycling back into the raw material stream. These tiles go one step further, each labeled with a phone number and website for reclamation instructions. Designing for disassembly is a crucial step towards a circular construction sector.

Merlijn Blok, Built Environment Consultant at Metabolic, says materials passports play a particularly valuable role at the design phase. “Material passports support architects in conceptualizing buildings as material banks from which valuable products can be harvested after the buildings, or part of the buildings, become obsolete,” he says. “By designing for disassembly and archiving information on the materials we’re adding to our built environment, architects can play a crucial role in sustaining a waste-free circular economy into the future.”

Existing buildings can get passports too

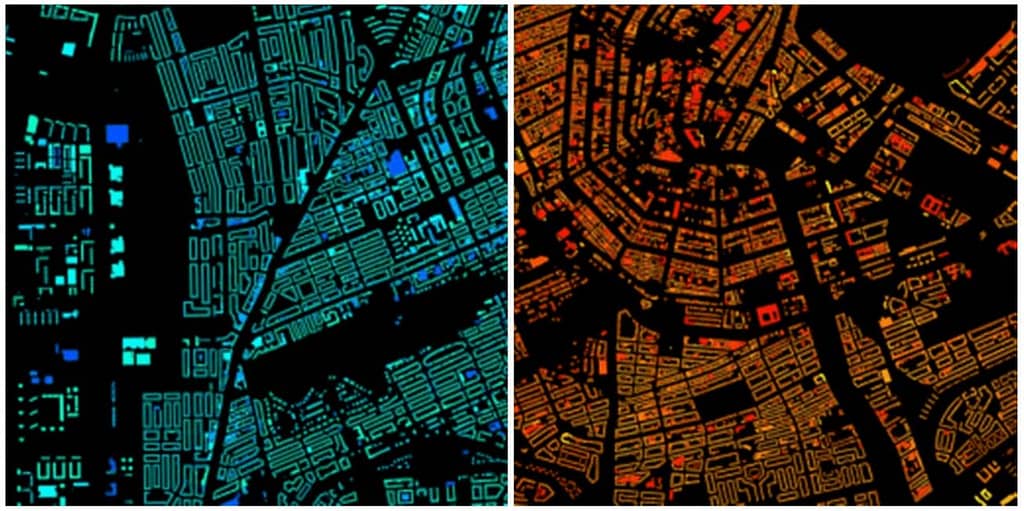

Ideally, a materials passport is created before a building is constructed. But they can also be developed for existing buildings, through techniques such as plan analysis, and digital 3D scanning. These analyses can help building owners to understand the quality of the materials already in use in their buildings, and the lifespans of specific materials, informing timely maintenance. These analyses can be applied on a larger scale than just individual buildings, for instance, estimating the metal content of buildings across Amsterdam. There are plenty of possibilities for this to be taken further down the track. BAMB Material Passport Best Practices guide envisions augmented reality platforms allowing auditors and surveyors to walk through buildings and view data drawn out of material passports superimposed on the components they are looking at.

In the Netherlands, two of the biggest real estate owners are housing corporations and governments. Almost one third of all the houses are owned by housing corporations, while the government owns twelve million square metres of building surface area. Since materials passports can provide insights into exactly what a building is made of, they can also play a significant role during maintenance or renovations, which typically happen on three different types of occasions.

- Ad hoc (when something breaks and needs fixing immediately)

- When a tenant leaves the dwelling

- On a structural basis (based on the maintenance and inspection calendar)

The last two types of maintenance, in particular, benefit from material passports to reduce environmental impact and make the process more efficient. Without such a document, a lack of information and time generally means a one size fits all approach: stripping a lot of materials which might not have reached their technical end of life. Since no information on their status is easily accessible, they are discarded. A case-by-case assessment is not practical at these large scales. Incorporating material passports into maintenance plans could lead to significant sustainability gains during renovation and maintenance. Material passports can highlight the state of these materials and prevent the discarding of these materials or (if large quantities are present) can help to find new uses for these materials and components.

Encouraging sustainable decisions

Ordinary home owners also benefit from materials passports. Buying a house which has been lived in for many years becomes significantly safer if there is a document showing the history of the house and all past renovations, as well as all the components used in the house you are about to buy, their quality, potential impact on a healthy living environment, and even how they were mounted. Ideally, this access to information would also incentivise market forces: people should be more willing to buy a home or apartment if they know exactly what materials are inside, where they came from, and just how environmentally friendly they are. In turn, this would encourage new buildings with lower impacts and better materials, since these buildings might go for a premium. The better we can record the history of the materials, the further down the supply chain the incentive spreads. These incentives can also be encouraged, for example by providing tax benefits to buildings with reused materials.

Facilitating urban mining

On a larger urban scale, all the information from thousands of materials passports could add up to a very detailed understanding of what materials are available in the city. Having access to this information makes it easier for municipalities and developers to use existing materials from demolished or dismantled buildings. Matching the demolition calendar to the building/development calendar with a thorough understanding of the available materials and their status is a big booster for re-using these materials at their highest possible value. This process is known as urban mining: treating a city like a mine where valuable materials exist and can be extracted.

The downsides: why materials passports are not yet universal

As interesting as materials passports are, they are not perfect. Integrating a powerful new tool which will have such profound impact on the building sector also brings serious challenges. These challenges have slowed their adoption and implementation in the construction sector.

Lack of a unified approach

Many different parties are developing their own passports, with different types of documentation, different visions, and goals. Although this does increase complexity, this is not an inherent problem as long as these passports are able to communicate with each other. If, for example, a re-used beam is traded between organizations which use different standards, then the information will need to be translated. This can be a costly additional step, and if the two organizations have different passports and different levels of material detail, components and history, then two key advantages of the passport – the ability to create a unified maintenance schedule and knowing the life-cycle of each component – could be lost. There is no perfect passport, since there will always be a trade-off between detail, time and cost. There are initiatives aimed at solving the challenges of unification, but it will take engagement from the construction sector, government, and industry with a period dominated by trial and error.

Keeping up to date

A good materials passport includes information on maintenance, replacements, and changes to the building. This in turn means keeping the document up to date, which may not be a challenge for home-owners who are invested in their property, but can be a serious hurdle for big corporations, governments and even renters. If they repaint the living room, what paint did they use? Where did they get it? Maintaining a high level of detail can be difficult over time.

Privacy and security

Everyone’s personal passports should be kept safe and secure. So should building passports, for many of the same reasons. In an increasingly digital world this might not be as easy. Clear sharing and privacy guidelines on the information in the passports and how to share it (and with whom) are essential for making optimal use of a material passport’s value. Finally, the information needs to be trustworthy. The fourth owner of a building or a component, needs to be sure that the information about materials and their supply chain has not been changed by any of the first three owners. This requires investment in an independent agent that everyone can trust, or a system like blockchain which makes earlier information almost impossible to retroactively edit.

Towards a circular economy for construction

Given how fast we are creating new buildings around the world, there has never been a better time to adopt materials passports. By enabling circular economic practices that extend the lifetime of building materials, materials passports could fundamentally reshape the business models that underpin the construction sector, and economy at large. Dutch architect Rau envisions how material passports can make components for buildings into something that is not always bought, but can also be loaned as a service. “All that is physical in a closed system is a limited edition in essence, and, thus, it has a value,” he says. “We have limited materials and it is service, not ownership, that facilitates the way we use them in an unlimited way. If we really want to change the world, we must change business models.”