As nations juggle COVID peaks and troughs and attempt to reopen their economies, world leaders face another set of pivotal decisions: how to recover and rebuild. With thousands of livelihoods at the mercy of a massive economic downturn, relief is urgent. But as we connect the dots on the structural vulnerabilities at the root of this crisis, it’s clear that symptomatic solutions will not be enough. To prevent and prepare ourselves for future shocks, we must address the systemic issues that make our world increasingly fragile – and rebuild with greater resilience.

‘If today’s short-term measures to reopen economies do not promote long-term economic resilience… the next disaster will be only a matter of time.’

The Global Resilience Imperative

This pandemic has knocked us off our feet, with the world’s most vulnerable communities bearing its brunt. At this juncture, we have an opportunity to reevaluate our direction of travel and build an economy that is inclusive and resilient in the face of future turbulence.

Genuinely ‘building back better’ means approaching our understanding of the COVID crisis through a systems lens to understand root causes, connections, and consequences. It also means approaching pathways out of this crisis through a systems lens, looking at effectiveness rather than efficiency, avoiding unintended consequences, and managing trade-offs.

As we chart a way forward over the coming months, we call on world leaders to embrace the long-term effects of their actions, and to ensure that these immense challenges are addressed as interacting systems, instead of in isolation. To do so, systems thinking is one of our most powerful tools.

A new risk landscape

“We are not living in a linear, Newtonian world where actions cause predictable reactions. We are in fact part of a complex system of environmental, socio-political and economic systems that we are constantly reconfiguring and that is constantly affecting us.”

New Approaches to Economic Challenges

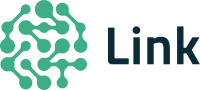

The far-reaching impacts of COVID-19 have revealed structural vulnerabilities within our global socio-economic system. Over the last half century, machines and fossil fuels have enabled human systems to develop at an exponential rate. While this has come with significant socio-economic advances, it has led to new pressures on human and environmental health.

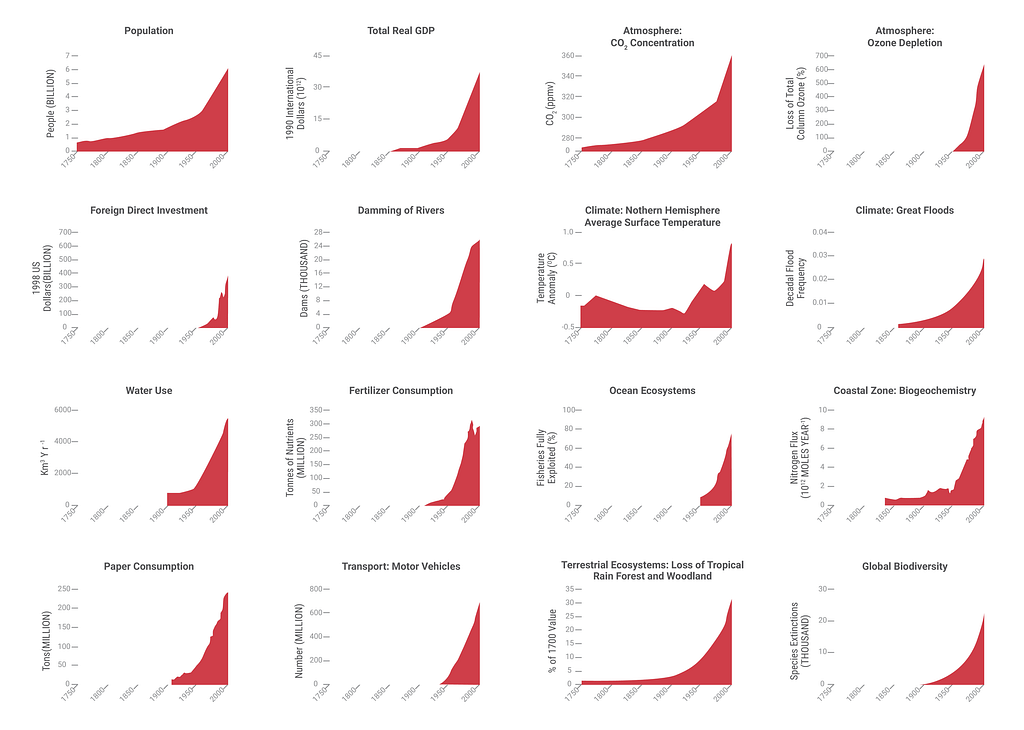

It has also created a new risk landscape, fostering the necessary conditions – weak points in our socio-economic immune system – that enable a pandemic like COVID-19 to take hold and wreak catastrophe. These conditions have been well documented by leading thinkers in science, policy, business, and finance over the past months:

- Destruction and exploitation of nature: Zoonotic diseases are becoming increasingly prevalent as our hunger for space and resources puts pressure on natural ecosystems and drives new forms of contact between people and wild animal species. Professors Josef Settele, Sandra Díaz and Eduardo Brondizio, and Dr. Peter Daszak, note in an IPBES guest article that “rampant deforestation, uncontrolled expansion of agriculture, intensive farming, mining and infrastructure development, as well as the exploitation of wild species have created a ‘perfect storm’ for the spillover of diseases from wildlife to people.”

- Overuse of our global commons: Human health is linked to planetary health. As we continue to transgress the planet’s safe limits through extractive and wasteful economies, we threaten the natural life-support systems that keep our planet stable. As Johan Rockstrom and Ottmar Edenhoffer of the Potsdam Institute explain, global risks such as pandemics “are directly linked to a scarcity of global public goods such as disease control, as well as to overuse of global commons such as clean air and water, a stable climate, biodiversity, and intact forests.” Malfunctioning global commons in the form of polluted air and lack of access to clean water have acted as threat magnifiers of the pandemic, worsening its effects.

- Wealth and income inequality: Marginalized populations are bearing the brunt of this pandemic. People from disadvantaged backgrounds often have little or no access to healthcare and health insurance, don’t have the luxury of being able to work from home, are more reliant on public transportation, live in polluted neighbourhoods more prone to the virus’ effects, and have no financial buffer or safety net in the case of unemployment. As the WBCSD writes, “inequality acts as a ‘threat magnifier,’ interacting with the spread of the virus in ways that increase the vulnerability of society as a whole.”

- Highly efficient, highly fragile supply chains: A recent survey by the Institute for Supply Chain Management reported that 97% of organizations have been or will be impacted by the COVID crisis. This is not surprising when much of the world relies on international supply chains for essential goods and services. As noted by the OECD, the “concentration of industrial capacities and economic activity… has produced highly lucrative yet fragile supply chains.” Compounding this fragility is a lack of buffer capacity and flexibility to absorb a supply chain disruption. A decades-long emphasis on inventory reduction, cost-saving, and efficiency in the form of ‘just-in-time’ supply chains has left businesses woefully unprepared for supply disruptions in China – “the world’s factory” – and a lockdown on international trade.

- Failure of global governance: COVID-19 ‘exposes a basic contradiction between an enormously complex planetary ecosystem and our still dominant form of political organisation: a fragmented system of sovereign states,’ writes Tom Pegram of UCL. Member states have left the WHO immensely short of the US$3.4 billion a year that is needed to fund “global functions” of pandemic preparedness. Nations tackling COVID in isolation, in service of their own interests, have quickly come to terms with the inevitably global nature of this crisis. As some nations commandeer the finite pool of medical apparatus needed to manage the disease effectively, others lack strong leadership and state capacity to manage remaining hotbeds for the pandemic to remain in circulation.

Systems and resilience: a bird’s-eye view

Digging deeper still, the conditions fuelling the catastrophic effects of COVID-19 – and other systemic threats – are rooted in the way our global systems are structured. Understanding how these systems are designed can shed light on why our society and economy functions as it does, and how this has led to a fundamental breakdown in resilience and long-term sustainability.

The efficiency trade-off

Resilience looks at how systems respond to disturbance or stress. A system that can anticipate, adapt, and reorganize itself to keep functioning under conditions of adversity – such as a global pandemic – is a resilient one.

As COVID has shown, one of the most fundamental threats to the resilience of our economic system is its primary calibration towards efficiency. As noted by Roger L. Martin, ‘resilient systems are typically characterized by the very features – diversity and redundancy, or slack – that efficiency seeks to destroy.’

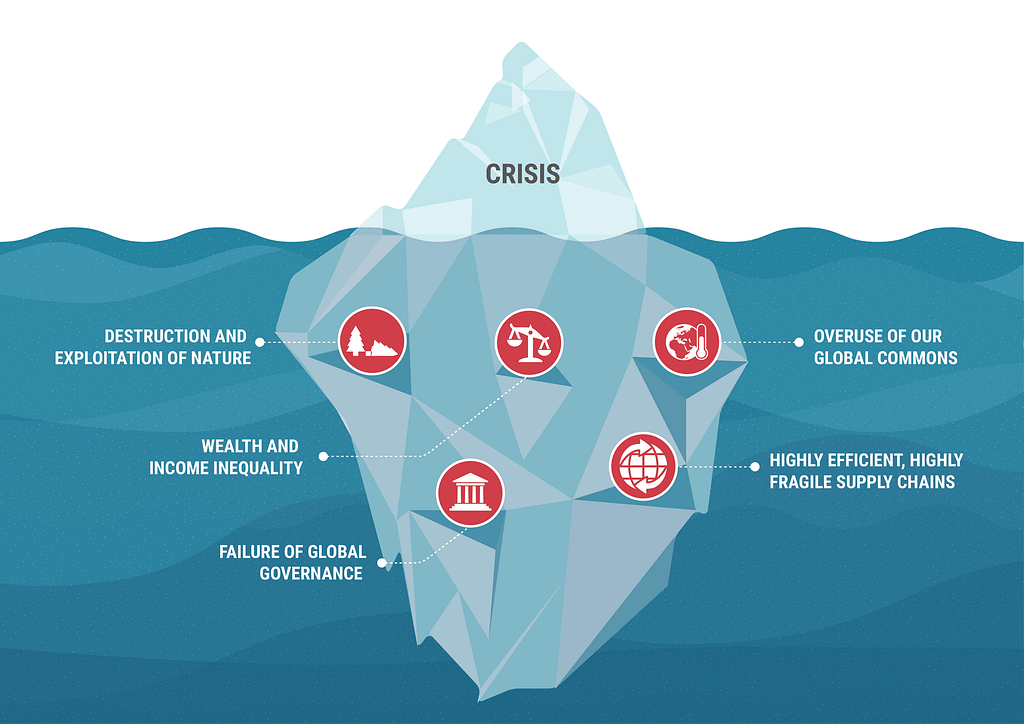

Today’s large-scale, specialized, and centralized supply chains are highly efficient and cost-effective, but their corresponding lack of diversity and distributed interconnectivity leads to a few single points of failure. If the system fails, it is so highly optimized and rid of redundancy that no buffers exist to keep it functioning during recovery.

This fine-tuning towards efficiency is driven by a global economic system focused on short-term profit maximization. When the sole purpose of corporations is to maximize shareholder returns, a dangerous feedback loop is created where short-term financial successes come at the expense of long-term resilience.

Moral hazard

Linked to this short-term profit addiction is a tendency for organizations to take risks that maximize financial returns. In an economy that relies on corporate bailouts during times of crisis, companies are incentivized to take even greater risks — shifting to just-in-time supply chains, not keeping cash-on-hand, and relying on highly lucrative, yet highly risky corporate loans. This ‘moral hazard’ increases the fragility of businesses, decreasing the resilience of the corporate sector as a whole, and making it more likely that the government will again have to bail them out when the next crisis strikes.

Unequal by design

The COVID pandemic has exposed an economic system that is designed to concentrate wealth and magnify inequality. The ‘success to the successful’ system archetype explains how unequal access to wealth and opportunities results in a reinforcing feedback loop that drives a perpetually widening global inequality gap. In the last 30-40 years, the global top 1% earners have captured twice as much of global income growth as the 50% poorest individuals. This has led to the world’s richest 1 percent owning 44 percent of the world’s wealth. How does this relate to crises like COVID and our resilience to future shocks? Unequal economies create a lack of resilience – when the vast majority of people don’t have a buffer to weather any kind of crisis, inequality becomes everyone’s problem, destabilizing the system as a whole.

Tragedy of the commons

The pressure we are putting on public goods and common resources can be understood by a systems phenomenon called the ‘tragedy of the commons,’ otherwise summed up as ‘individual gain, collective pain.’ In a global economy that rewards competition, common resources invariably get overexploited as we aim to maximize individual gains from a shared pool. Communitarian societies and institutions with a strong tradition of common resources often had strong cultural, social and legal structures in place to foster cooperation rather than competition. However, our current global economic system has eroded many of these structures, rewarding competition over cooperation and short-term gain at the expense of common resources. If everyone maximizes individual gains, the commons becomes overloaded and we all experience diminishing benefits. Since the time frame of the commons “collapse” is much longer than the time frame for individual gains, we are eroding our life support systems in favour of short-term rewards.

An economic growth addiction

In their April 2020 Covid response, the Global Environment Facility wrote: “Economic growth during the last half century has disrupted ecosystems through unplanned urbanization and expansion of human settlements at rates higher than population growth.” And not all are benefitting equally from this growth. The conundrum? With GDP as our primary indicator of success, we have created a society so dependent on economic growth that if it doesn’t grow, it collapses. In the case of COVID, ‘flattening the infection curve inevitably steepens the macroeconomic recession curve’ highlighting the degree to which social stability and welfare depends on growth” notes the WBCSD.

Building back genuinely better

Governments are making $10 trillion available in crisis recovery stimulus packages. How leaders decide to allocate this capital now will define socio-economic recovery over the coming decades. Relief is urgent and funds must alleviate the immense human suffering this crisis is causing. But the systemic risks of an ever more unsustainable and unequal economy pose future havoc, perhaps of much greater proportions. A new WEF report finds that, should ‘business as usual’ continue, $44 trillion (over half of global GDP) is potentially threatened by nature loss. With the COVID crisis as our yardstick, the corresponding threats to human welfare are gut-churning.

As the EU Commission notes, ‘the opportunity of getting out of the crisis greener and fairer cannot be wasted in the name of urgency.’ Governments, business leaders, policy makers, investors, and civil society are pledging their support for strategies that, instead of returning to a flawed ‘normal,’ aim to build back better. Just this week, more than 60 countries promised to put wildlife and climate at the heart of post-COVID recovery plans.

To genuinely fulfill this pledge, we must break the feedback loops that drive structural vulnerabilities. Building systemic resilience to future shocks means governments should prioritize policy measures and spending to:

Build systems thinking approaches and tools into decision-making

COVID-19’s myriad knock-on effects are a palpable reminder that global health, social, and economic systems are deeply intertwined. To effectively build resilience within and across these interacting systems, we must depart the ‘traditional, linear, compartmentalised way of making and applying policy’, as the OECD notes, and build capacity towards a systems thinking approach. In charting a long-term sustainable recovery, systems mapping and modelling processes can help to better understand connections and causal relationships, evaluate trade-offs, and predict effects that may not be obvious at first glance.

Restore natural ecosystems and the common goods they provide

Dismantling the driving forces that, left unregulated, will collapse our global commons requires collective stewardship. Cross-organizational, -sector, and -governmental collaboration must be incentivized, so as to gather and share timely data on the state of earth systems. This is critical to minimize the feedback delay between resource depletion and actions. Science-based targets should be broadly adopted, allocating countries, cities, and organizations their sustainable share of resources on a finite planet. Rollbacks of environmental protections must be avoided, and stimulus support made conditional on environmental sustainability commitments. Pivotally, fiscal policies should be designed to reflect the true costs of economic decisions. With fossil-fuel industries already downsizing due to all-time-low energy prices, now is the time to cut fossil fuel subsidies and introduce a carbon tax.

Encourage business to think and act long-term

To prepare for future shocks, companies will benefit from thicker inventory and cash buffers – a shift from just-in-time to just-in-case thinking. Policy can play an important role in encouraging this shift. As advocated by Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s antifragile approach, governments should make sure that ‘manufacturing, transportation, information, and health-care systems have redundant storage and processing components.’ To disincentivize excessive short-term risk-taking, corporate bail-outs should be accompanied by dividend and bonus payout bans.

Systems that endure achieve a dynamic balance between efficient performance and adaptive resilience. The NAEC recommends developing methods for quantifying resilience so that trade-offs between a system’s efficiency and resilience can be made explicit and guide investments. Graphic source: Lietaer (2010)

Stimulate circular economies in high-impact sectors

We can dramatically increase the resilience of key human systems such as cities, food, and manufacturing by closing local resource loops and decreasing reliance on imported resources. Circular economic principles like remanufacturing, repairability, and reusability can bring stability in the face of volatile global supply chain challenges, including, but not limited to, the urgent supply of medical equipment. Longer term, circular economies will help governments achieve climate goals and deliver broad societal benefits.

City municipalities will benefit from creating more distributed, local production capacity and developing regional supply chains. To achieve this, a significant portion of stimulus funding should be routed toward building circular economies from the ground up. The unusual economic situation is uniquely suited to leveraging this available capital in ways that help tackle barriers to a circular transition and reduce investment risk for new, circular enterprises. To do this, we propose the creation of government-supported, impact-focused blended finance facilities that can jumpstart regional circular economy transitions.

Promote international collaboration

An instinctive reaction to the COVID-19 crisis would be to try to limit global connectivity. But for many reasons this will only make dealing with systemic threats harder, including finding a vaccine and driving systemic socio-economic recovery and adaptation. An open letter from the Planetary Emergency Partnership writes, “international cooperation is the best option to resolve future existential threats. Like Covid19, climate change, biodiversity loss, and financial collapse do not observe national borders. These threats must be managed through systemic and collective action.”

To steer our whole earth system towards absolute optimal outcomes requires collective understanding of systems connections and complexity – for example, how a specific action in one country might affect the resilience of the global economy as a whole – and custodianship of common resources.

“Rather than countries competing with one another, we should remember we are agents of the global whole working on behalf of all inhabitants on Spaceship Earth.”

Tom Pegram, UCL

Drive structural economic reform

Many of the problematic conditions that we have outlined in this paper – the destruction and exploitation of nature, the pervasive growth of inequality, the fragility resulting from excessive efficiency – can all be causally traced back to the incentives built into our current economic system. The economy as it is currently structured will inevitably concentrate wealth in the hands of a few, reward short-term thinking, and continue to grow at the expense of human wellbeing and ecological health. Ultimately, to succeed at building back better, we must build back differently. If we simply focus on job creation and economic growth in the old paradigm, the same patterns that led us to this crisis will be maintained and new crises will emerge.

We need to fundamentally change the rules of the game. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has long been recognized as a flawed metric for the monitoring of national progress. It is time for us to embrace more comprehensive indicators centered on human wellbeing and ecological health as a measure of our success. We need to build in essential failsafes against runaway concentrations of wealth and create genuine social safety nets. We need to reexamine our commitment to economic growth as a central objective. These are not new ideas, but it is time for them to become mainstreamed and implemented – or at the very least tested more broadly. We need political leaders who are not afraid to put forward a new, more hopeful vision of the future and break with the stagnant and damaging mantras of the past.

Conclusion

While an immense tragedy, COVID has the potential to ignite a revolution in the way that we relate to one another and the biological world. The sudden and dramatic nature of this crisis has stoked a sense of urgency and an openness to change; it’s easier to take bold action when the entire world has unwittingly been thrust into a large-scale experiment. However, instability and shortage of resources can also trigger the desire to hold on to familiar realities and well-worn lines of reasoning.

We must resist the desire to fall back into old, reductionist ways of thinking. The oversimplified view of our world that has dominated our decision-making has long stood in our way of understanding the long-term consequences of our actions and policies. Our socio-economic system is complex, multi-layered, and deeply intertwined with the natural world on which we depend for our livelihoods. We need to take the time – especially now – to look at our world anew using the lens of systems thinking. Only by understanding the deep interconnections between institutions, people, and the environment will we be able to craft pathways toward a genuinely sustainable and resilient economy; one that works for all people and supports the flourishing of all living beings.