Can a modern multinational company reshape its value chain to preserve nature, rather than deplete it? The answer is yes.

Even the largest of operations can work to stop using more ecological resources than the planet can provide. Metabolic’s work with Bel Group, a large agrifood company, is proving just that: there are concrete ways to reduce the damage to biodiversity — and even restore it.

When company founder Jules Bel started producing cheese in Eastern France’s stretch of the Jura Mountains in 1865, the earth’s supply of land and resources was still able to withstand the population’s demand. Over the next 150 years, Bel Group, the food firm his family still runs today, would expand globally and become famous for Babybel, The Laughing Cow, Boursin, and Kiri, some of the world’s most popular cheeses.

As the company grew, so did the industrialized world’s demand — and its environmental impact — on nature. Biodiversity is declining at a rate not seen since the last mass extinction, and this crisis poses a risk to human health, the global economy, and the survival of businesses.

“When you are a family business, transparent, sustainable practices are essential,” Bel Group Sustainability Manager Marie-Laure Eychenne said about Bel’s commitment to centering Mother Nature in its broad sustainability strategy. “We are aware that each of our operations can have an impact and that we depend on biodiversity and its preservation. We have the responsibility of feeding the 9 billion people on the planet by 2050, while also preserving the planet’s natural resources.”

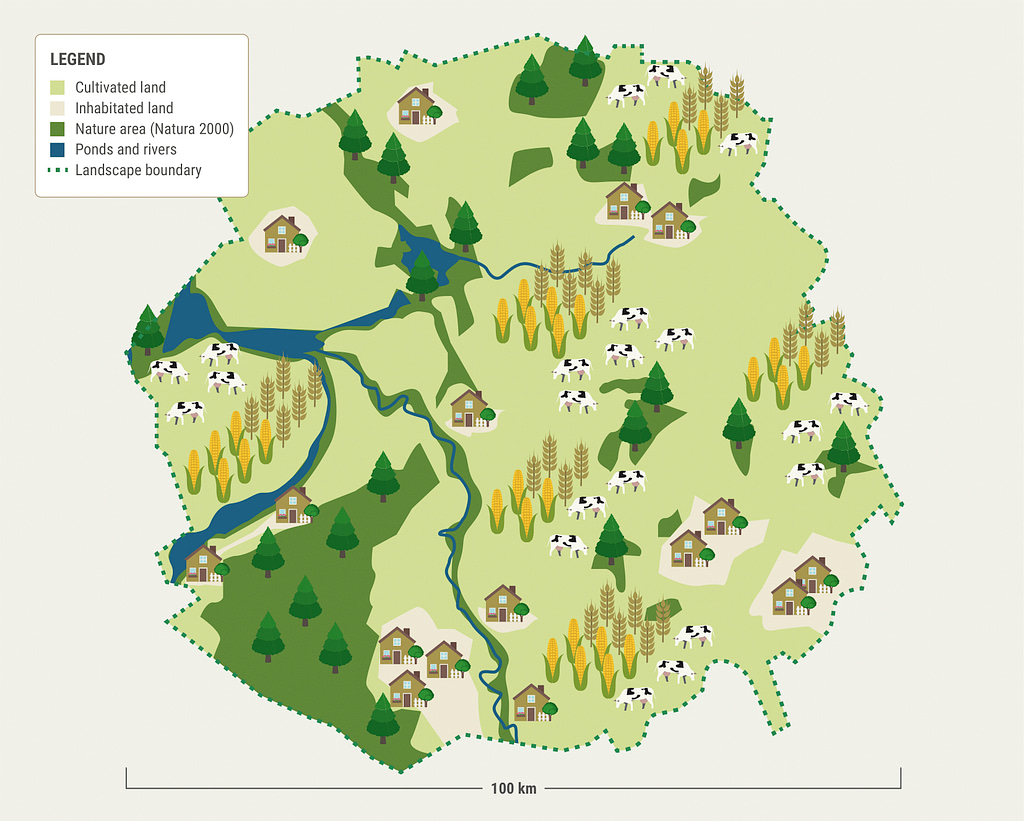

But any well-intentioned corporate strategy calling for value chain transformation that champions biodiversity is a complex mission. It needs proven, scientific guidelines. This is why Bel Group enlisted Metabolic’s team of agrifood experts to create an action plan addressing biodiversity loss and soil/water usage while preserving species and ecosystems. This plan shows Bel what areas of its procurement and operations to target and where it can make the most positive impacts on biodiversity. We analyzed the operations of just one of Bel’s dairy basins in the Netherlands, but the findings can be applied across all its agricultural landscapes in Europe.

“The statistics we uncovered reflect a comprehensive understanding of a company’s impacts and dependencies on nature, from direct operations to full value chain and associated spheres of influence,” said Louisa Durkin, a biodiversity and agrifood systems expert at Metabolic. “This is critical to addressing environmental externalities and essential for catalyzing the process of internal corporate transformation.”

Combining Bel’s primary data with science-based methods, the Metabolic team uncovered aspects unique to Bel Group’s broader, ecological story that culminated in a holistic, systems approach to large-scale dairy production.

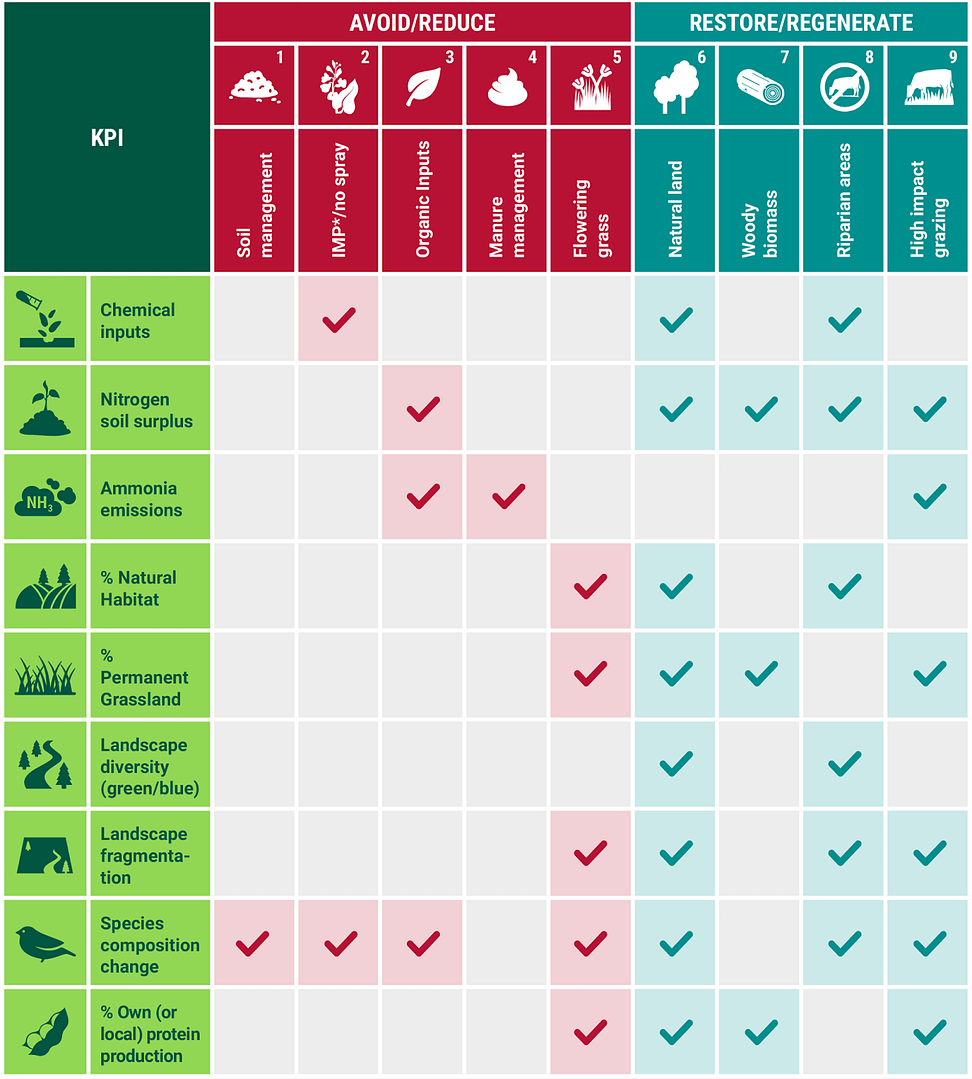

The assessment showed areas where implementing regenerative agricultural practices can help to reduce the performance gap on farms in the dairy basin. For example, Metabolic’s research detected gaps for: ammonia emissions, chemical (pesticide, herbicide, fungicide) inputs, nitrogen soil surplus, percentage of protein production, and percentage of natural habitat. The framework advises first addressing actions that avoid and reduce impacts, then the actions that restore and regenerate.

Our researchers examined pathways to improve the business case for farmers that want to close the gap on any farm level targets not being met. They identified how a whole-of-society approach can support and incentivize farmers to make the transformation toward farming that improves biodiversity/nature. This information can drive future corporate decision-making for any firm that relies on nature to do business.

“The challenge is from the farm to the fork,” said Eychenne. “We want to act responsibly all over our value chain. This starts upstream with raw materials — cheese, milk, apples — to our production chain, and to the end of life of our packaging.”

Metabolic’s full report outlines the various interventions that could move the basin’s landscape towards nature-positive outcomes. The team also created a database of activities that avoid/reduce pressures on ecology, revealing specific methods for Bel Group’s operations that can restore and regenerate ecosystems. To do that, we looked at the material impacts on nature relevant to the dairy industry. Working with the World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) France, we identified local ecological thresholds in dairy farms to determine what is really needed to enable ecosystem resilience and avoid collapse. We then identified societal goals for key performance indicators, and we used farm census data to set best practices to reach these goals.

These are transformative, yet attainable, solutions backed by the scientific community and the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN), a large consortium of nature-related NGOs, companies, and mission-driven organizations that founded the climate-focused Science Based Targets initiative. Its mission is to build an unparalleled protocol that will arm companies across many sectors with the appropriate scientific tools for creating an equitable, nature-positive, net-zero future.

Bel is among dozens of SBTN members actively contributing to the corporate engagement program, spearheading science-based targets (SBTs) for nature and sharing best practices with anyone aligning their business with ecological thresholds. Bel Group will share Metabolic’s findings and their own progress to implement new methods with other SBTN members who want to create a company strategy toward nature-positive outcomes.

Nature is the keyword in all of this work. So dire is the pressure on ecology that targeting climate is no longer enough.

“We have to deal with nature and climate at the same time,” said Juliette Pugliesi, WWF France’s natural capital officer and the Biodiversity Hub coordinator at SBTN. “We use the science-based targets method addressing climate change and extend it to nature. The consortium counts more than 60 partners and 100 companies. Having such a wide network is a strength because it allows us to involve all ecosystems and players to reach a scientific consensus on how to restore oceans, freshwater, land, and biodiversity.”

What makes the undertaking so impressive is that there is no single unit of measurement for science-based targets for something as geographically diverse and locally complex as nature. (SBTs for climate change are measured in standard units of carbon and applicable globally.) To set targets for nature, other dimensions also need to be considered, such as water use, water pollution, land degradation, and direct resource exploitation. Metabolic demystified this during our research for Bel.

Change is more promising once a company can grasp the many dimensions. While Jules Bel cannot witness this evolution today, his successors, the fifth generation of the Bel family, are hopeful for a future where farming and biodiversity go hand in hand.

After all, without nature, there will be no business. Over half of global GDP is dependent on healthy ecosystems and the services they provide. It’s increasingly clear that society cannot meet climate goals if we do not also take ambitious action and bend the curve on nature.

The SBTN’s formal guidelines are collaborative and a work in progress, but they do advise universal, “no-regret” interim targets that companies can set now: avoiding deforestation, reducing water withdrawals in high water impact areas in a company’s value chain, and restoring ecosystems within its sphere of influence.

“Bel is showing implementation is possible,” said Durkin, as the company undertakes interim targets specific to its industry and to the landscapes where its dairy operations operate. “We are providing a template for anybody who needs an entry point, a holistic way to approach target setting. The success of the SBTN requires pioneering companies to get going today and make the science-based target-setting process for nature a reality.”

Learn more about Metabolic’s role in the project.