At Metabolic, we use systems thinking as a core strategy to advance our vision of a circular and sustainable economy. From Thailand to Burkina Faso, here are two examples of how this approach delivers sustainable solutions.

By looking at the world around us as a whole rather than as independent parts, we can understand how the different actors in a system are connected. We can examine the inter-relationships, look for patterns, and seek the root causes of problems. “Systems thinking underpins everything we do,” says Eva Gladek, founder and CEO of Metabolic. “The essence of systems thinking is that you don’t look at an object on its own, you consider everything that it is connected to.”

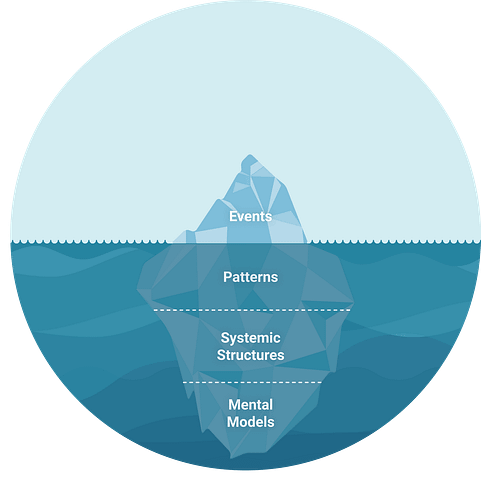

Most of today’s biggest challenges have deep and complex roots in our system that go beyond just what we can “see.”

“Addressing the root causes of a problem is fundamental to creating a positive, systemic impact,” argues Andrew McCue, from our Cities and Industries teams. “We deal with this complexity because it allows us to find the key leverage points, avoid unintended consequences, and create long-lasting change.”

Using systems thinking enables us to see beyond the immediate impact of one solution. Importantly, this allows us to be aware of unintended consequences and avoid shifting the burden from one problem to another.

Thailand’s plastic soup crisis

Our Zero Plastic Waste Thailand project is a useful example to better understand how this works. The project took a science-based approach to build a circular economy for plastics and to ultimately reduce the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean.

Thailand’s Roadmap on Plastic Waste Management 2018-2030 identified ambitious targets to decrease the amount of plastic leaking into nature. For instance, by the end of 2022 the country aims to eliminate the use of thin plastic items, such as bags and plastic straws, and achieve 100% recycling of targeted plastic wastes. Yet, we identified a lack of legal restriction and enforcement on the use of plastic bags and on requirements for manufacturers around the types of plastics they use.

If the government were to go ahead and require companies to reduce the amount of plastic they use based on simple metrics such as the mass of plastics used, companies may create packaging made of very thin plastic or multiple materials. These may contain less plastic, but they are also almost impossible to recycle. This creates a knock-on effect of reducing recycling rates overall and can ultimately lead to more litter.

Thailand’s government faces a challenge to avoid creating an environment where companies only look for a plastic solution that could “beat” producer responsibility rules, explained McCue, who worked with the WWF on this project in 2020. By not taking exceptional care to shape incentives in the right direction, producer responsibility policies can just “shut one possible polluting door,” he said, leaving the rest of the doors open. This creates a huge risk of burden shifting.

How we applied systems thinking

When analyzing the plastic waste problem in Thailand, one of our team’s first steps was to understand the system and how all of the actors (political, economic, social, infrastructural, commercial) fit together. We started by evaluating the flows of plastic packaging materials at each stage of the waste management chain and then matching the country’s needs with best practices in producer responsibility from around the world. Using a “causal loop analysis,” we identified one of the main root causes of plastic waste, namely that the lack of producer guidelines or regulations for packaging materials led to the proliferation of “lightweight” and multi-material packages that are not profitable to recycle. We were able to suggest action points to shape change without causing further unintended consequences.

We designed the system map (below), which shows the underlying causes of plastic waste, and how seemingly unrelated factors actually result in increased plastic waste and litter.

In order to achieve sufficient impact reduction, we recommended that new policies, fees, and incentives should be tied to both mass and to the embodied environmental impact of materials. In fact, the fees must be based on the true costs of waste management and environmental impacts, taking into account factors such as recyclability and life cycle assessment (LCA).

Improving Burkina Faso’s cacao sector

Our systems thinking approach ensures our solutions will last over the long run and avoid creating “fixes that fail”, i.e. short-term solutions that actually create new problems or otherwise erode the original goal.

This approach proved particularly valuable in our work with Burkina Faso’s Centre for the Promotion of Imports (CBI), a Dutch agency that supports developing countries by expanding their exports to Europe. We were asked: how can Burkina Faso have sustainable and inclusive growth? We analyzed the natural ingredients value chains in Burkina Faso, focusing specifically on the opportunities within the agricultural sector for non-timber forest products like shea, moringa, and baobab, untangling the complex interactions within the regional value chain. On the surface, increasing the export of natural products and also the yield productivity could appear to be a fitting solution, bringing a higher income, food safety, and more work to local farmers.

Such an intervention would initially create a minor boost in farmers’ earnings. However, over the long term, a narrow focus on yield would actually lead to damaging farming practices like monocropping and overuse of fertilizers and pesticides. These can lead to long-term problems such as soil degradation, nutrient loss, and groundwater pollution. Furthermore, an economy focused mainly on promoting export would eventually mean less food available for the local market, higher prices, and thus food insecurity locally.

With a systems thinking hat on

We looked at the whole system to find long-lasting solutions for the country’s supply chain problems. We mapped the system (see below) to visualize the relationships between the different parts and identity leverage action points, such as the export of carbon credits in the moringa sector.

Instead of focusing on maximizing yield productivity and exports, we suggested something completely different: establishing a carbon offset program in the moringa sector.

Moringa trees are known for their nutritional and medicinal properties. They also sequester carbon above and below ground, so they hold potential for carbon offsetting to mitigate climate change. This can reduce climate-related ecosystem degradation, such as soil erosion, and fertility loss, which are known problems in the agricultural sector.

The recommendation from our team is ecologically sound for the future. It has the potential to boost local food security through increased income and increased supply. Monetizing carbon sequestration of moringa as a service could also enable the export of carbon offsets, adding value to the moringa sector without impacting the food supply. Most importantly, it removes the risks of price increases associated with exporting products.

Identify leverage points to have the greatest desired effect

With systems thinking, we identify the ‘levers’ in a system. These “leverage points,” as described by Donella Meadows, a recognized environmental scientist and systems thinking proponent, are places where a small shift in one area can produce big changes across the system.

In the two projects that we just looked at, our teams used systems thinking to assess the whole system and find leverage points.

Creating long-lasting change, finding leverage points, and avoiding burden-shifting are more than just practice, explains Erin Kennedy, the lead of our Circular Raw Materials Systems work. “ It’s a complete change in mindset, one that we are exercising every day in our team,” she says.

At Metabolic, we use systems thinking as a core strategy to advance the vision of a circular and sustainable economy. This approach is visible in the structure of our work, our theory of change, and our ecosystem. In fact, our mission to transition the global economy to a fundamentally sustainable state, cannot be achieved by focusing on one single element at a time. With our systemic approach, we are able to identify leverage points to have the greatest desired effect.