Is your city or region doing enough to reduce carbon emissions and ecological impacts? The key is to measure not only what is produced there, but also what is consumed.

The environmental impact of a city or region reaches far beyond its borders. Much of what is consumed inside a city is produced somewhere else – often in a low-income country. According to the UN, a person in a high-income country consumes more than 13 times as much as someone in a low-income country. So an accurate assessment of the impact a city or region – or a country – is having on the world environment must take into account the effects of all the goods and services consumed, not only produced, in the region. This is especially important in high-income countries with very high consumption levels.

The city of Boulder in Colorado, for instance, plans to reach zero-emission by 2050, via a Climate Mobilization Action Plan that Metabolic fed into the development of. The plan gives a picture of all the materials being consumed, transformed, and wasted in Boulder. It turns out that the emissions embodied in imported products – mainly electronics, clothing, and textiles – are higher than all local sources of emissions put together. That means that even a small change in the amount of “stuff” the city of Boulder imports and uses can have an enormous effect on overall carbon emissions.

Boulder is not a special case, either. In a 2019 study of nearly 100 of the world’s big cities, C40 Cities found that 85% of the carbon emissions associated with goods and services consumed within the city boundaries were imported from elsewhere. This has huge implications for emissions reduction. “The place to start is with those who consume the most”, the report noted, pointing out that in order to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees celsius, urban consumption-based emissions have to be halved by 2030. And that’s just taking into account the effect of consumption on carbon emissions, not the impact on biodiversity, land-use, or any other planetary limit.

Materials for mobile phones, for instance, often come from all over the world. The materials are shipped, processed, and the phones are eventually assembled quite far from many of the consumers. Greenpeace has estimated that the amount of power used in the production of smartphones since their commercial release in 2007 is equivalent to the power used in a year in India. And the tin, tantalum, and tungsten used in the phones are mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo by workers as young as 10 years old making an average of 1 US dollar a day and working without health or safety standards. All of this constitutes “upstream impact”, an impact that occurs before consumption. After consumption, the waste may be processed and shipped somewhere else again, leading to more indirect, “downstream” impact on the environment and on people.

A production-based approach to carbon emissions, for example, would count all emissions produced in a city or region, no matter where the goods and services produced are consumed. A consumption-based approach counts all the emissions embodied in goods and services consumed in the city or region, no matter where they were produced. As David Roberts points out in a Vox article, “the former captures exports; the latter captures imports. The two inventories overlap in that some goods and services are both produced and consumed within the city”.

There may also be some overlap on the global scale. Products may lead production-based emissions in one city, on one side of the world, and also add towards the consumption-based emissions of another city where they are consumed, on the other side of the world. For that reason, properly tracking and minimizing impacts from consumption should be complementary, it should not entirely replace production-based analysis. Ideally, cities should be measuring both, to make sure impacts are minimized, and are not exported to more vulnerable regions of the world.

Consumption-based emissions can be more difficult to measure than that of production – it is challenging for a city or region to track every single product imported or exported and its associated emissions. Estimating consumption emissions associated with products is much more complex than, say, energy. Instead, you have to use broad categories of goods and their average carbon intensities. Tracking and reducing consumption-based emissions thus relies on good data. Other ecological impacts, such as impacts on biodiversity, water, and land-use can be harder still. However, with the right approach and the right data sources, it is possible to get an increasingly accurate picture.

The next question is, how low should a region’s consumption-based impacts really be?

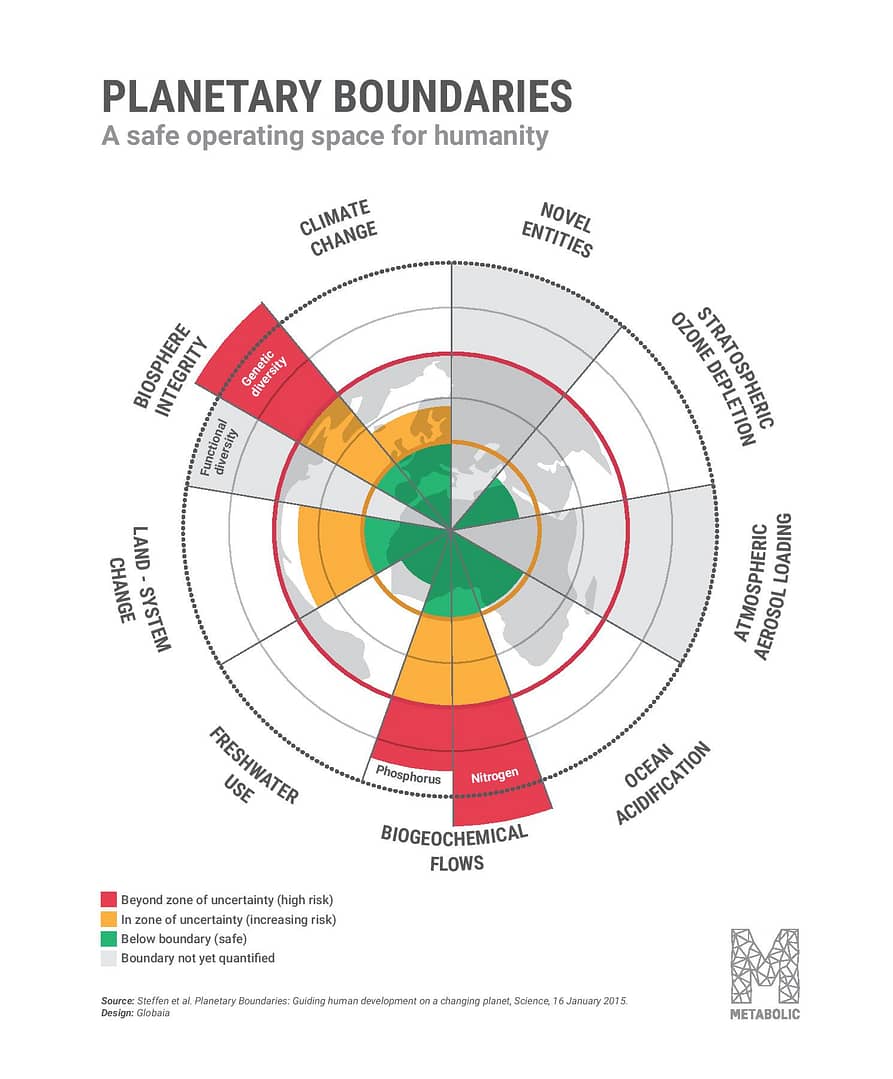

One way to define the safe limits for a city or region is the use of planetary boundaries. The planetary boundaries framework, first developed by the Stockholm Resilience Center in 2009, maps out key environmental systems within which the earth should remain stable, livable, and healthy, and where humanity can continue to develop and thrive. Inside the boundaries is our “safe operating space”. The most recent estimate suggests that four processes – climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change, and biogeochemical cycles – are at increasing risk of triggering fundamental and undesirable Earth system changes.

Each of these boundaries is intricately connected to the others, and risks within one boundary cannot be dealt with in isolation. Using more land infringes on biodiversity and also reduces natural carbon storage, which in turn exacerbates climate change. Worsening climate change in turn puts pressure on environmental systems as well as agriculture, which forces an increased use of fertilizer like nitrogen and phosphorus, and land. Planetary systems are connected, but so are social systems.

These boundaries can be calculated at a regional – or city – level, defining the “safe” limits to the impact of region or city. The Science Based Targets Initiative and Science Based Targets Network are working with companies and cities to define specific targets and guidance, so as to ensure their activities fit within these absolute boundaries. This is done by allocating the maximum share that a region can have of the global safe operating space.

Once the “safe” share has been calculated, this can be compared with the actual consumption-based impact of a city or region, to reveal how well the city or region is really doing. And the results can be surprising.

Using this approach, the Netherlands, for instance, has already calculated that they are in ‘unsafe’ and ‘clear unsafe’ levels on all five selected parameters in a study .

Combining the planetary boundaries with consumption-based impact measurement can be a powerful tool for change. Planetary boundaries provide future-proof and science-based targets, and a consumption-based footprint allows us to measure the full impact of a region or city. Used together, these two methods offer an accurate evaluation of the true impact on the world of what is being done in a part of it.

High impact areas, or ‘hotspots’, can then be identified by comparing the city’s or region’s actual consumption-based impact with its boundary allocation.

Where the thresholds are exceeded, action is needed.