Is Europe living within the limits of our planet? A recent report by the European Environmental Agency and the Swiss Federal Office of the Environment aims to answer this question. Mapping the environmental footprint of the continent in relation to the planetary boundaries framework, it shows that Europe is indeed exceeding its limits. Interestingly, the largest shares of many countries’ environmental footprints occur abroad.

Earlier this month, two authors of the report joined Professor Johan Rockström on a webinar to discuss global and regional environmental limits, and how to return to a safe operating space. The discussion opened with the fact that the world is facing “three interconnected crises: a climate crisis, a health crisis, and an ecosystem crisis”. Responding to these crises requires targeted action from business, policy, and civil society, and the planetary boundaries framework, mapped by a team co-led by Professor Rockstrom in 2009, can provide necessary guideposts for development.

What are planetary boundaries?

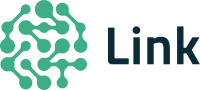

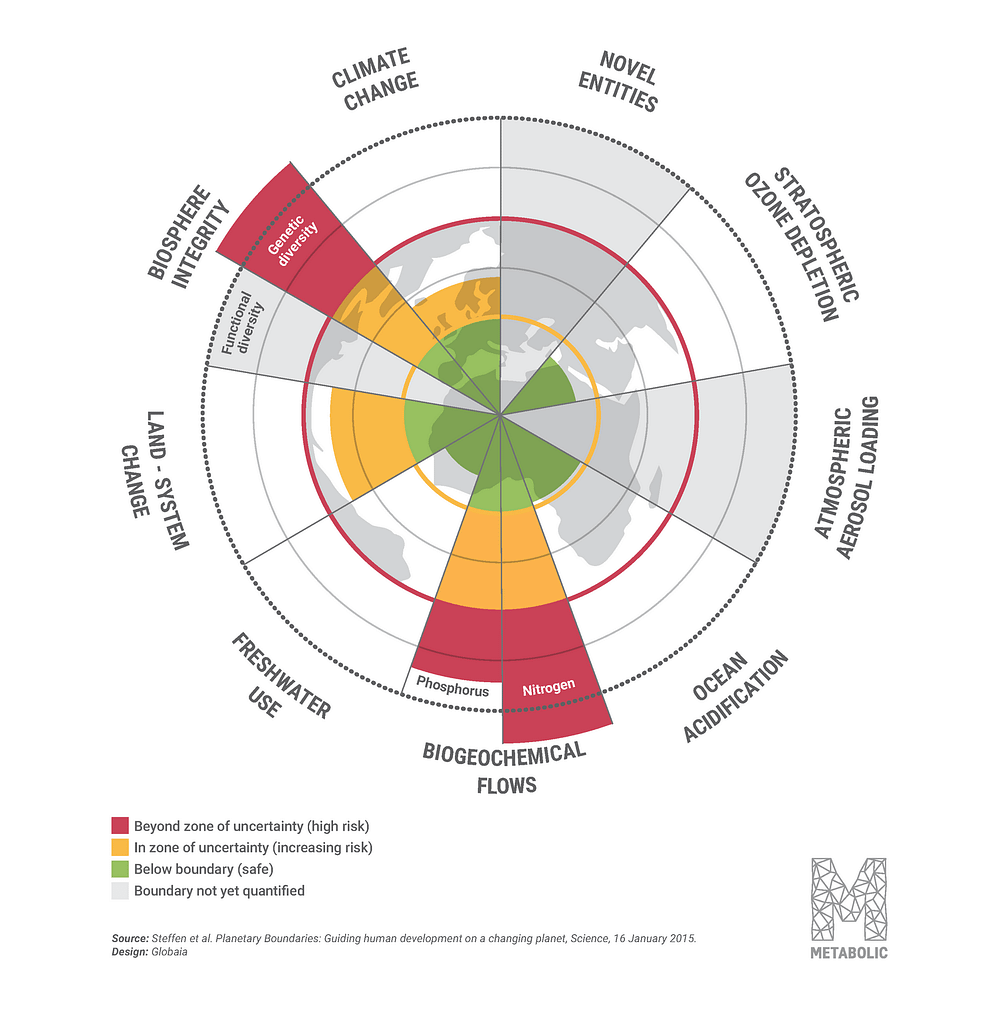

The planetary boundaries map out key environmental systems, within which the earth should remain stable, livable, and healthy, and where humanity can continue to develop and thrive. Inside the boundaries is our “safe operating space”. The framework identifies nine processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system. Rockström explained that the framework was partly a response to the great acceleration of the 1950’s, in which our economies, our consumption, our use of materials and land, all started to grow exponentially. In contrast to this unstable growth, Rockström wanted to know what the earth would need, to remain in a stable equilibrium. The most recent estimate suggests that four Earth system processes – climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change, and biogeochemical cycles – are in a zone of increasing risk of triggering fundamental and undesirable Earth system changes.

The planetary boundaries are central to our work at Metabolic, as we help companies, cities, and NGOs work towards impactful sustainability strategies.

Each of these boundaries is intricately connected to the others, and none can be solved in isolation. Using more land infringes on biodiversity and also reduces natural carbon storage, which in turn exacerbates climate change. Worsening climate change in turn puts pressure on environmental systems as well as agriculture, which forces an increased use of fertilizer like nitrogen and phosphorus, and land. Planetary systems are connected, but so are social systems. As the webinar revealed, COVID-19 is not a black swan; pandemics, extreme events are reflections of a hyper-connected world.

How then, can we connect the science of planetary boundaries to pathways for the future? The process is two-fold: reduce the planetary boundaries framework to a regional level by understanding how much impact Europe can have without tipping the scales, and then measure Europe’s actual impact as accurately as possible.

Reducing planetary boundaries to a regional scale

Applying the globally defined planetary boundaries framework to Europe requires a definition of Europe’s shares of the global safe operating space. Matching planetary boundaries to a regional scale means touching on the difficult issue of allocation. The report explores five different allocation principles ranging from per-capita to needs-based allocation, and the right to development of poor countries which are further from SDG targets. Bringing these calculations together results in an overall European share of 7.3% of the global limit, while a per-capita allocation would result in an allocation of 8.1% of planetary limits. In other words, to be within planetary limits, Europe should contribute less than 7-8% of a sustainable global carbon footprint, less than 7-8% of an acceptable biodiversity impact, and less than 7-8% of a reasonable global nitrogen budget.

Measuring embodied impacts with a consumption-based perspective

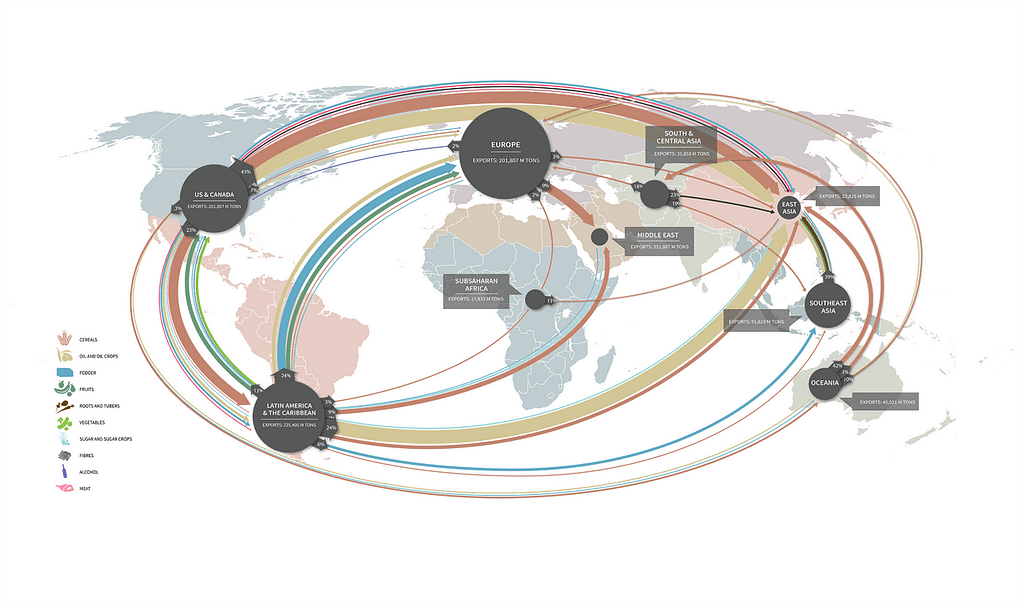

Knowing the regional limit, the other side of the coin entails accurate measurements of European environmental impact. Traditionally, environmental impacts have been measured by adding up the impacts of all the industries and activities within a certain boundary. Products produced elsewhere and imported were not counted, even if they were consumed inside the region. For high-income countries with more imports than exports, this allowed a kind of loophole: export production overseas, and your environmental footprint would be lower. This is where a consumption-based footprinting approach comes in. A consumption-based approach means looking at the environmental impacts that have happened as a result of using a product, material or service. It includes the impacts of the supply chain (upstream) and the impacts of the disposal (downstream).

This approach is increasingly important in a globalised world, as high-income countries increasingly rely on lower-income nations for raw materials and products, and more impact takes place outside of national boundaries than within. It is also important for cities, which rely on regional imports. C40 Cities recently mapped out the consumption-based emissions of their partner cities and found that 80% of the participating cities are “consuming cities”: their emissions related to consumption are higher than local emissions. Our work with Boulder, Colorado revealed similar trends.

Three boundaries overshot

The report “is Europe living within the limits of our planet?” examined four boundaries: nitrogen and phosphorus, two key “biogeochemical” flows which are crucial to soil health; as well as land-use.

3 of the 4 boundaries have been overshot. Nitrogen and phosphorus were particularly heavily overshot, by factors of 3 and 2 respectively, with implications for the food system. Compounding this pressure, the land-use boundary is also overshot. The use of freshwater was not, but Lung cautioned that this European-level indicator might disguise water scarcity issues on local or national levels.

Where to go from here?

As Rockstrom put it, we need to achieve prosperity and equity in the planetary boundaries. It is increasingly clear that we are delivering well on social indicators at the expense of the planet.

As the report argues, the European Green Deal provides an opportunity to fundamentally take on the idea of ‘living well, within the limits of our planet’ by addressing the social and environmental needs of Europe in a holistic manner, paying attention to the interlinkages between environmental targets, and between social and environmental systems.

The report also makes it clear that Europe will need to transform the systems of consumption and production, if we are to address the underlying drivers of unsustainability. The specific boundaries addressed in the report and the webinar – the nitrogen cycle, the phosphorus cycle, land system change and freshwater use – are deeply connected with the larger food system. In other words, transforming the food system is not only an important step, it is the key to making deeper changes across multiple boundaries; it is a “leverage point”.

There are already growing calls for the EU to develop a ‘common food policy’. The European Green Deal envisages a ‘farm to fork strategy’ on sustainable food along the whole value chain, which provides exactly such an opportunity to build a comprehensive policy framework and to put Europe on a clear path towards living within environmental limits.

To learn more, read the report summary here.