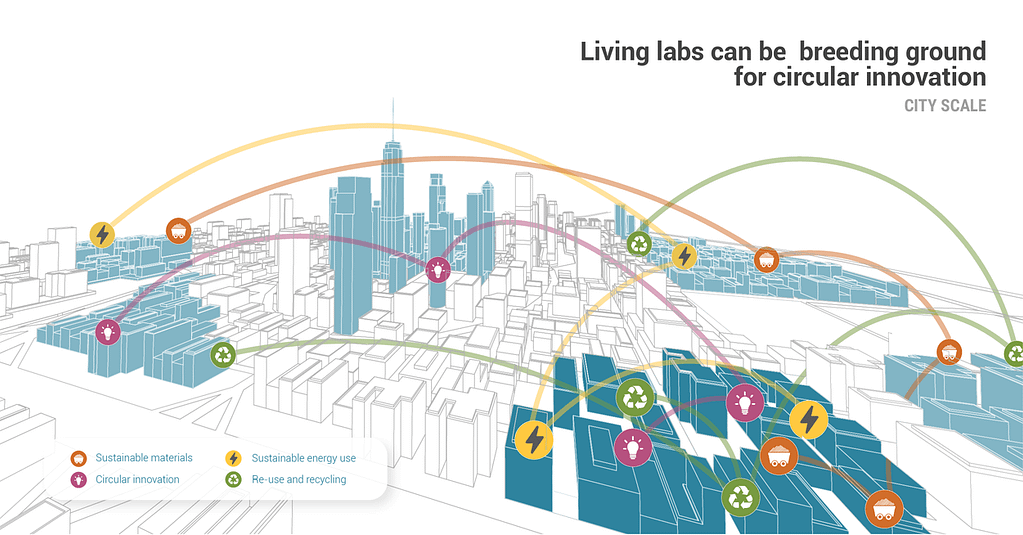

As the world urbanizes, cities are both vulnerable to climate change and in a powerful position to lead the transition to combat it. Cities from Amsterdam to Charlotte, North Carolina, are embracing experimentation through urban living labs. These user-centered, open innovation ecosystems demonstrate that starting on a small scale can go a long way toward driving circular innovation in urban areas.

Small, successful experiments now are better than great plans for tomorrow

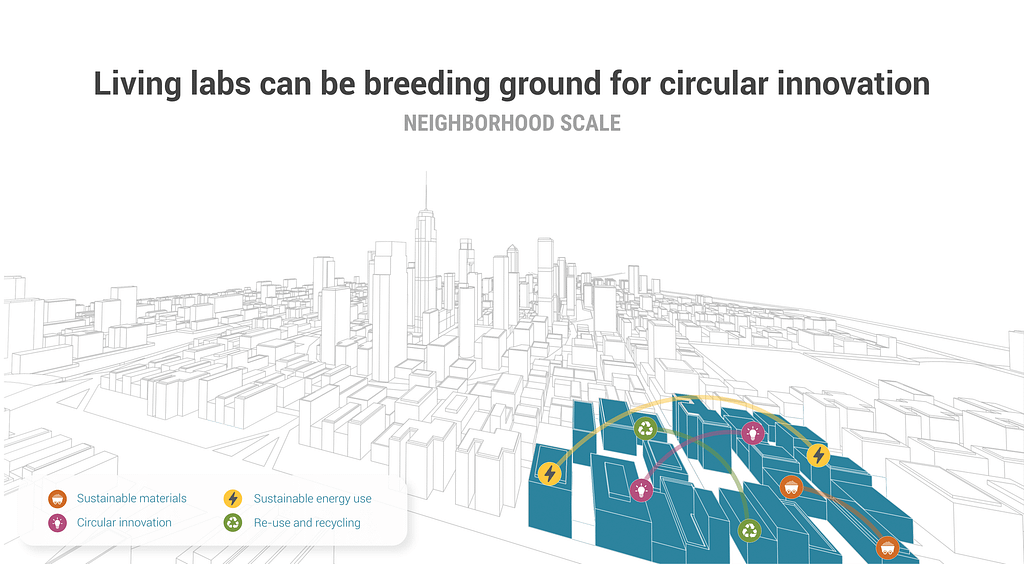

More and more cities have ambitious plans when it comes to the circular economy, but bringing them to life can be a challenge, especially at scale. This is where living labs come into play. They are a vehicle for exploring, testing, and refining real-life solutions to urban challenges. Like “minimum viable products,” which is a working model of a product for a small set of beta users, living labs can be seen as “minimum viable ecosystems” for testing the core features of a circular economy in a smaller and simpler urban context. This might be a neighborhood or a business incubator, like the Charlotte Innovation Barn, which recently opened. Experimenting in such an ecosystem with manageable boundaries allows municipalities, businesses, and citizens to demonstrate circular principles in action. They can also gain a deeper understanding of circular interventions in practice when seeing how different parts of a system fit together. The learnings from these real-world experiments are visible products for the public to witness, and they can be the basis for bigger urban strategies.

“Showing that something works, or doesn’t work, and why, is so much more valuable than just an idea, concept, or rendering,” says Chandar van der Zande, a consultant at Metabolic.

The district of Buiksloterham, in Amsterdam, is home to two living labs: The sustainable floating neighborhood Schoonschip and clean-tech playground De Ceuvel. Both sites serve as testing beds for circular strategies, particularly for the transition to local, sustainable energy production. At Schoonschip, extracting heat from the water in the canal, generating local photovoltaic power, and using proper insulation and energy-efficient equipment are among the many measures it is taking towards energy neutrality. To spur similar circular innovations in Amsterdam, all of the findings and knowledge are open source and accessible via their “Greenprint” platform. The motto is: demonstrate, then replicate.

Similarly, De Ceuvel piloted the blockchain-based energy sharing platform “Jouliette” to test and demonstrate how locally produced renewable energy can be shared, stored, and managed. The microgrid pilots are now being used on a wider scale, and they have been integrated into one larger energy community portfolio as part of a global showcase for creating positive energy districts.

Breeding ground for circular innovation and entrepreneurship

The best experiments do not happen from the top down, but within a healthy environment where local innovators and entrepreneurs can thrive. The city of Charlotte, aspiring to become the first circular city in the United States, created a living lab dubbed the Innovation Barn to stimulate local innovation for utilizing local waste streams. By providing equipment, expert advice, and commercial feedback, the Innovation Barn encourages entrepreneurs to tap into the city’s urban mine. Examples include recovering nutrients in food waste using black soldier fly production, upcycling wood and establishing a chain of custody using TreeID, and converting collected bio-waste into new materials – like clothing, furnishings, and biodegradable packaging.

While living labs act as a playground offering room to test a broad variety of things, it is important to make strategic choices. To drive entrepreneurship effectively, living labs need to be targeted.

“I see living labs like a bull’s eye with lots of layers, but at its core, you have to be clear on what you are researching and what it is a lab for,” says Chris Monaghan, our founding partner and Ventures director. “Make choices on what it is trying to do, how it is interacting, and what it is really trying to test.”

In the case of the Innovation Barn, the first step in building entrepreneurship is focused on testing new value propositions around plastic waste. Currently a pilot program, the Plastics Lab is responding to the rise in single-use plastics due to the pandemic by collecting non-recyclable takeout food containers from Charlotte residents and turning them into filament that can be used in 3D printers. Due to the current demand, the filaments are then used for the top part of medical face shields. Post-pandemic, the Plastics Lab will allow local innovators to divert plastic waste from landfills by creating new prototypes and products.

Facts don’t change our minds. Experiences do.

Practitioners and scholars are increasingly highlighting the importance of experimental spaces as convincing ways to show the potential a circular economy holds for cities. “Facts,” as John Adams put it, “are stubborn things, but our minds are even more stubborn.” Instead of reading about circular cities, people can experience them in living labs. Demonstrable examples like these have the power to turn the circular economy concept into a living experience, creating curiosity and interest in the concept across the globe.

This rings true at De Ceuvel. By closing as many resource cycles on site as possible, the site serves as a proof of concept to urban professionals worldwide of how resources can be managed in a city. And for citizens, it is an invitation to be inspired and engage when visiting spaces like De Ceuvel’s Cafe, which serves edible plants grown in a closed nutrient loop at its aquaponics greenhouse.

“As a result of this one small demonstration, dozens of cities around the world have been inspired to take more concrete action on moving toward a circular model,” says our founder and CEO, Eva Gladek. “We now have long-term relationships with three dozen cities around the world, helping them along their journey.”