Accounting for carbon emissions is essential to prevent irreversible climate change. To paint a full picture of environmental impacts, however, it is essential to go beyond carbon and account for soil, water, and biodiversity.

Every year since the middle of the last century, many farmers have become accustomed to engaging in the same cycle of practices to grow the food that feeds their families and the rest of us: tilling the soil, planting their crops, harvesting, then repeating the process. To meet the needs of a growing population and a global desire for affordable food, pesticides are often used to cheaply and quickly control insects, and fertilizer keeps yields up year after year. It’s remarkably efficient in the short term, contributing to an expansion of agricultural productivity that would have been almost unimaginable a century ago. While some farms are sustainable and have been for generations, and many more farms try to be, the global system is not. This global industrial pressure on farmland and soil places strain on some key planetary systems, and the food system is now one of the leading contributors to climate change, biodiversity loss, the steady erosion of soil quality, and freshwater use.

More than half of the earth’s total land surface is dedicated to agriculture, which includes croplands for grains, fruits, and vegetables, and pasture for livestock. Together, agriculture and forestry contribute to about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, depending on how it’s measured. And while awareness of—and commitment to change—agriculture’s role in environmental health has grown in recent years, actions and measurements have thus far focused on climate change. The effects of agriculture on nature go far beyond the carbon footprint.

The good news is, this creates a significant opportunity. Food production and processing companies hold the keys to some of the most transformative solutions for nature.

Climate change is a piece of the Planetary Boundaries puzzle

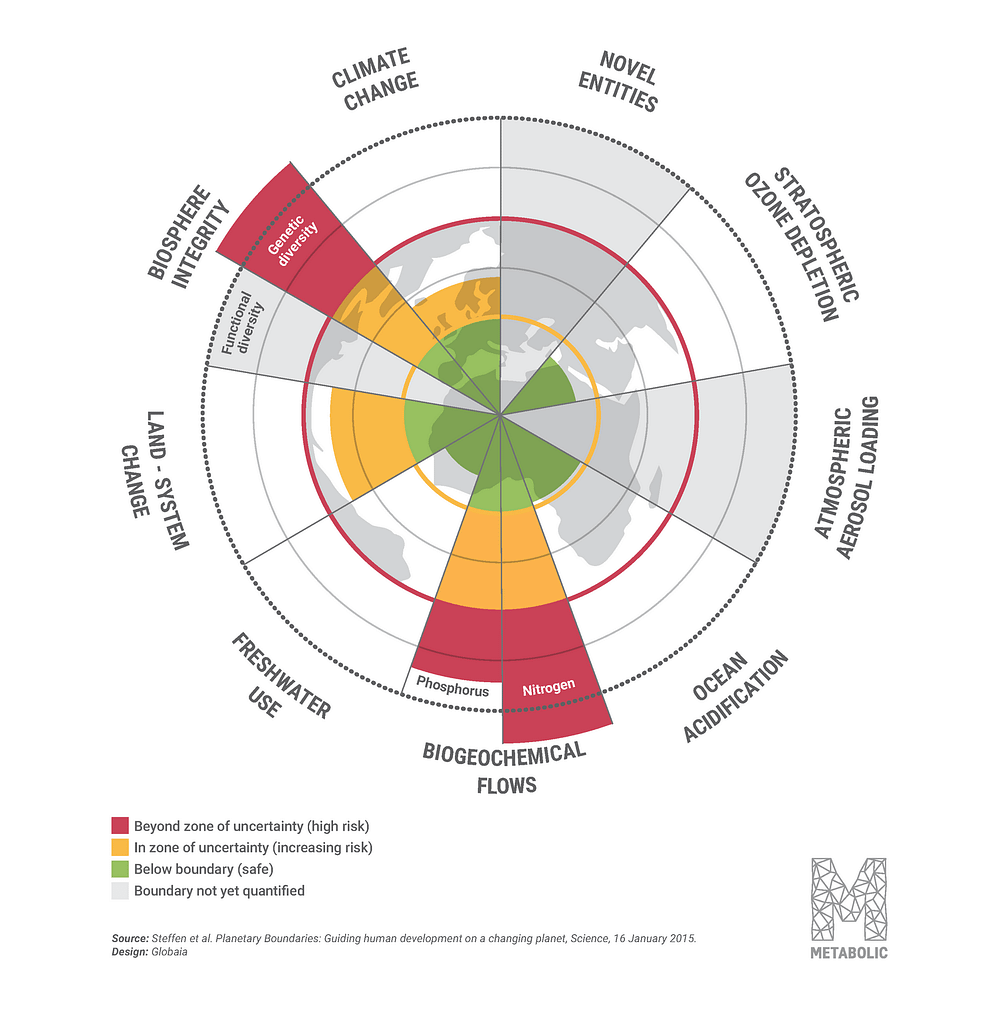

When we think of human impact on the environment perhaps our first thought is climate change. The two ideas have become somewhat synonymous. As penetrating as the climate crisis is, it is but one element of the environmental crises we face. Johan Rockström and colleagues at the Stockholm Resilience Center outlined in 2009 the concept of Planetary Boundaries: a safe operating space for human life on earth. They established thresholds for nine essential planetary systems; we have already exceeded one (biogeochemical flows, i.e. nitrogen and phosphorus pollution) and a component of another (biosphere integrity, or biodiversity). Climate change and land-system change are both on the verge of exceeding safe thresholds.

Agriculture contributes to at least six of these. Land-system change and biosphere integrity are nearest their limits—and with land-use change the number one driver of biodiversity loss, it makes sense to focus on them first. In the past 50 years, agricultural systems, especially large-scale, highly mechanized systems, have contributed greatly to both.

In 2012, ninety-four countries formed the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) to address global nature loss. Seven years later, the IPBES called for transformative change to protect nature—noting in the same report that land-use change is the number one driver of biodiversity loss. IPBES is biodiversity’s answer to the IPCC, but without policy agreement on what “protecting biodiversity” entails, setting targets will be tricky. There is good news on this front: in May 2021, a UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, China will aim to finalize the Global Biodiversity Framework. This framework has the potential to provide the same type of direct guidance the international community received from the Paris Agreement.

Setting targets for nature

In the meantime, companies are well placed to fill the gap. According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization and IPBES, likely the singular most important risk to identify in a supply chain is whether or not it is contributing to land-use change—particularly deforestation. In the age of information, it’s best to get ahead of the curve to identify risks and opportunities in a supply chain.

The first step is setting science-based targets. The Science-Based Targets Network (SBTN) recently released a guide on setting targets for nature. Over one thousand companies have already set climate targets under its rubric. Additionally, the Climate Disclosures Standards Board (one of SBTN’s members) has published guidance for nature-related financial disclosures. Adding up a business’s impact on biodiversity, land degradation, pollution, and water requires untangling more complexities than does accounting for carbon emissions. Nevertheless, we have all the tools we need to do so.

From targets to practice

Agriculture and food companies who want to implement practical solutions should consider the farm management practices of their suppliers and the social-environmental implications of their business models. To do this in a meaningful way requires traceable sourcing. Once the supply chain is transparent, mapping the risks and potential interventions becomes much clearer. The more detailed this sourcing information is, the more impactful the interventions will be. Once the risk profiles are identified through such top-down analyses, companies can create a plan to select and employ interventions. Ideally, these would address biodiversity effects, deforestation risk, soil health, pollution, health of watersheds, and climate impacts.

For example, we worked with Alpro to assess a network of their supplier farms in France and Spain. By getting right down to the level of individual farms, it became possible to assess both environmental impacts and the local carrying capacity. Could the region afford to use more water for irrigation, to reduce its land footprint without losing yield? In fact, improving biodiversity and reducing nutrient pollution turned out to be the more important interventions for that region.

A company might choose nature-based solutions like wetlands conservation or re-wilding marginal farmland for pollinators; might halt expansion in certain regions; or work with local NGOs to help determine the best social interventions in a region. Regenerative agriculture is another increasingly popular solution for high-impact producers. The concept is tried and tested: farming in line with nature has been practiced for generations. By mimicking nature in our agricultural system, it is possible to move away from synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and instead foster functionally diverse farmlands. When the biodiversity in and around farmland increases, nature benefits from less fragmented habitats, while producers reap the rewards of a balance of predators and prey, additional soil organic matter, increased pollination, and other services from nature.

In the private sector, it is becoming more and more common for businesses to describe themselves as “committed to Paris alignment”. Nature needs its version of the Paris Agreement. But there is no need—and no time—to wait. We already know many effective means of identifying and mitigating risks within supply chains, starting by preventing land-use change, ensuring traceable supply chains, setting transparent targets through organizations like the SBTN, involving local communities, and implementing regenerative agricultural practices. As we move away from extractive systems and towards measuring and working with nature, we will be able to enjoy her bounty for generations to come.