What happens to the plastic and paper that you’ve carefully sorted into separate bins?

We like to believe those old items are remade into new items and get cycled over and over again. In reality, most recycling is really ‘downcycling’. And while recycling, downcycling, and upcycling all help to preserve the life of raw materials and some of the value that went into creating them, there might be better ways to do it.

What’s the difference between recycling, upcycling, and downcycling?

Recycling is the process by which waste products are broken down to their basic materials, and remade into new products. Ideally, this should mean less need for virgin raw materials. Instead of mining or creating new raw materials, it should be possible to use recycled materials instead. Then, the energy, time and labor which went into extracting the raw materials would only need to happen once, and those materials would constantly be cycled and recycled.

In practice, not all recycling is created equal. Some countries include incineration in their ‘recycling’ rates, while some materials become less and less useful the more they are recycled, and so don’t necessarily displace virgin raw materials. In the end, most of what we refer to as ‘recycling’ is really ‘downcycling’.

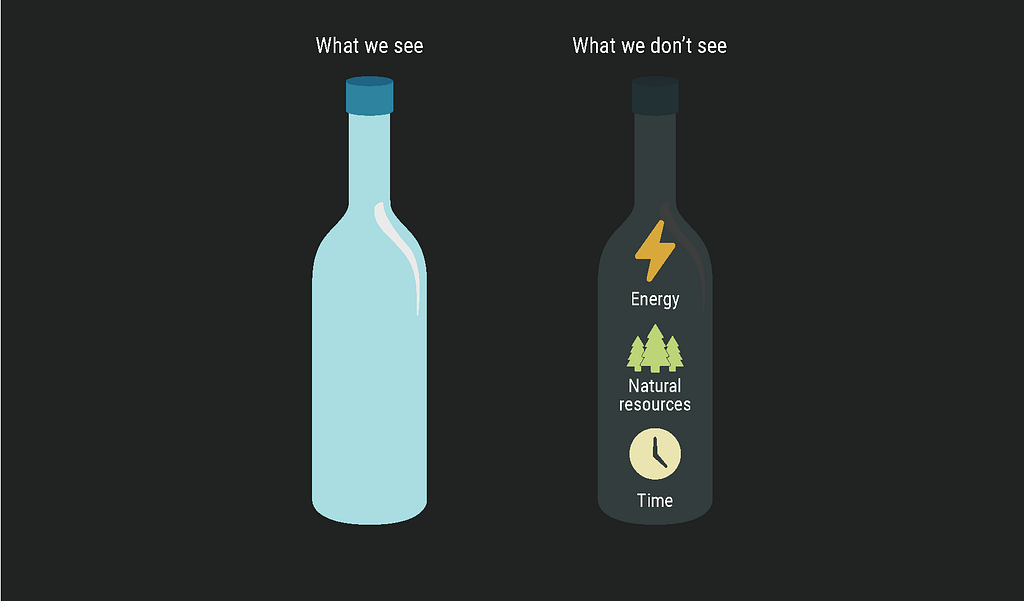

Products are carriers of embodied value

Before products are sold, raw materials first have to be extracted, refined into something more useful, then assembled into components, and finally into products. Every step along the supply chain requires natural resources, energy, labor, and time. Every step might require transportation, and every step might come with environmental impacts. The sum of these efforts is stored or embodied in a product. Every product has embodied energy, embodied impacts, etc. When a product is discarded at the end of its life cycle, all the effort and value that went into it is destroyed along with it. All forms of recycling are an attempt to preserve some of that embodied value. Not all of them do so successfully, however.

The nature of downcycling: value is not conserved

Downcycling begins the same way as recycling: products are broken down into their constituent materials and remade into something new. When those new products have less value than the original product, this is referred to as “downcycling”. For example, concrete can last for hundreds of years, but when old buildings are demolished, sometimes after a few short decades, much of the crushed concrete is downcycled into road filler: a cheap product with less value and less complexity than virgin concrete. This is not because there is any shortage of road filler, or any surplus of concrete, quite the contrary. Most of the time, it is cheaper and easier to downcycle than to recycle.

Some materials slowly break down each time they go through the recycling process, other materials tend to accumulate impurities. If the quality degrades every time we ‘recycle’ a product, it enters a spiral until its material is useless.

Examples of downcycling

For example plastic can recycle well, if it is properly cleaned and sorted. Plastic needs to meet three criteria to be recycled in most facilities: it needs to be able to melt without burning, it needs to be a single type of plastic, and it needs to be clean. Off-cuts in plastic product manufacturing plants are relatively easy to recycle. Real-world plastic products, however, might be made from a half-dozen types of plastic, often several in one product. Cleaning and separating all those into separate streams is nigh impossible, and although there are some promising ideas to do this automatically, most of the time the recyclable material ends up being of inferior quality and gets downcycled into simpler products, like doormats, carpeting, fleece, or even roads. These subsequent products are very rarely recyclable at all, which means that the chain is finite. We might reuse these materials once or twice, but they will not last forever, and sooner or later we will need new plastic.

Coming back to concrete, downcycling is relatively straightforward: destroy a building, take out the steel, wood and glass, crush the remaining rubble, and you’re done, and although the market for rubble is somewhat limited, it might be cheaper (and less damaging) than landfilling. Recycling concrete, however, would mean separating this rubble into the gravel, sand and cement from which it was made, and remaking a new batch of concrete. This might involve chemical processes, which in turn requires infrastructure and materials.

Paper is easier to sort and easier to recycle, and it is currently one of the most recycled materials. Europe claims to achieve a 73.9% paper recycling rate. However, it is much harder to remake high-quality writing paper into new high-quality writing paper. The fibers which make up paper become shorter and shorter during each recycling process, limiting their uses. Most recycled paper is downcycled into cardboard, tissue paper, and manila folders. New pulp from freshly-felled trees can be mixed into the process to improve the quality, and this does reduce the need for virgin pulp from felled trees. This process might save significant energy, though, depending on the amount of renewable energy in the grid, this might not result in direct CO2 reductions. Anything dirty (think pizza boxes) can’t be used at all.

Is upcycling better?

As we have seen, the cost of downcycling or recycling is a challenge. The value embodied in the raw material is conserved, but not the value of the product, and new energy and time have to be used to break down a product into recycled raw material and build it back into something new. When oil prices are low and labor is expensive, recycled plastic can be significantly more expensive than virgin plastic, and this can be true for other materials as well. One way around this is to incorporate the story of the materials into a new product, which often happens when upcycling.

Upcycling generally means simply turning a low-value product into a high-value product. Upcycling might not require breaking down the old product into constituent materials. For example, The Upcycle in Amsterdam hosts workshops to turn old bike tires into new belts, old shopping bags into notebooks. Broken bicycles and motorbikes can be remade into lamps and furniture.

Most of the time, the history of the waste becomes part of the story of the new product. Plastic Whale fishes waste out of the Dutch canals and remakes PET bottles into office furniture. The furniture (and the recycled plastic) is worth a premium, because of its history. This bypasses economic challenges to some extent, by enabling us to channel our societal desire for recycling into our purchasing decisions. However, upcycled products tend to be labor intensive, thus expensive, and while there will likely always be a space and a need for upcycling, it is unlikely to be a holistic solution.

Reducing consumption

Although downcycling is not perfect, it is generally preferable to landfill or incineration. Any kind of recycling helps keep materials in use, which can potentially reduce demand for some materials. Even downcycling paper and plastic into new products means that those new products don’t have to be created from virgin paper and plastic, and this comes with environmental benefits. For example, Dutch-based company Rebottled upcycles empty wine bottles into designer glassware. They have diverted over 140 000 glass bottles from going to waste to date. What’s more, the energy that was used to create the original glass bottles has been preserved. Rebottled has thus ‘saved’ at least 63MWh compared to the production process of new glass.

All types of recycling help to prolong the useful life of raw materials to some extent, and that’s no bad thing. Even new road filler means less sand and gravel is needed. But it’s not ideal, and there are better avenues to maintain the value of materials at their highest.

Beyond Downcycling: the need for a circular economy

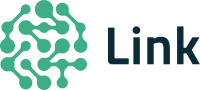

Recycling and downcycling preserve raw materials. But breaking a product all the way back down and perhaps building it all the way back up takes further energy and time and labor. While it is better to downcycle than to incinerate or dump the materials in a landfill, it would be better still to reuse the components or to refurbish the entire product. Reusing components would preserve the embodied value in the entire components, not just the materials. Repairing an entire product would preserve the time, effort, and transportation that went into assembling the components. What’s more, for complex products such as electronics, not all critical metals are recovered in the recycling process. By extending the life of electronics through reuse and remanufacturing, these valuable materials are able to stay in circulation.

This – the preservation of embodied value – is at the core of a circular economy. Supply chains are long and complex, and there is a lot of effort and potential environmental impact between extraction and retail sale. The closer to the retail side we can preserve a product, the more the complexity of the product is retained, the more embodied value is preserved and the smaller the environmental impact.

Current recycling targets encourage a blanket proportion of all materials to be recycled, for example, 40%. This is a very simple and necessary target, but it is incomplete. The next step is to incorporate more of the nuances about just how much value is conserved, how much virgin material is being displaced, and how much of that environmental impact we are saving.

The question, then, isn’t whether upcycling is better than downcycling. Conserving products at their highest level starts with repair, reuse, refurbishment, remanufacturing, and only if we cannot do so: recycling and downcycling.