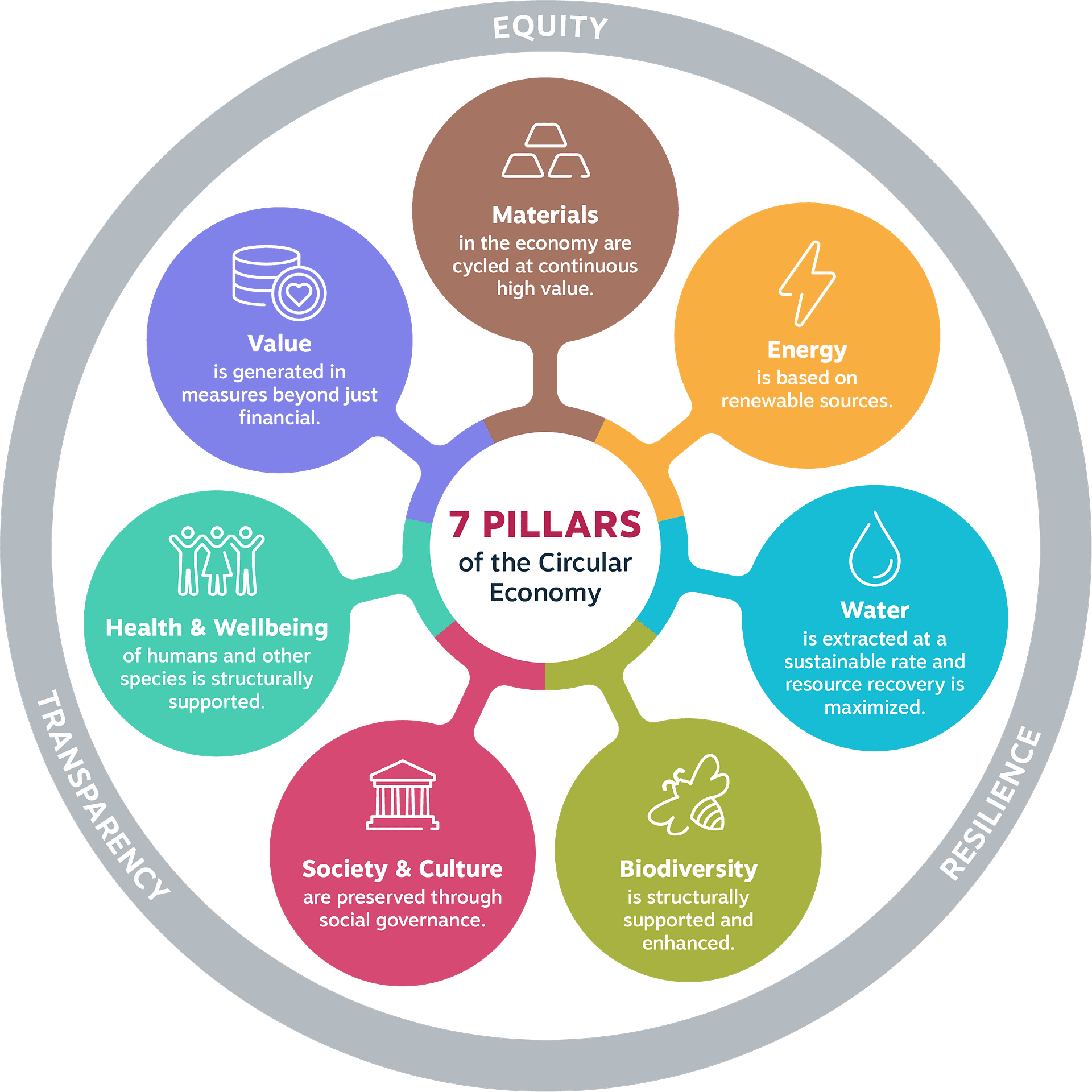

We can only define a circular economy if we look to the end state that we want to achieve. Metabolic’s Founder and CEO Eva Gladek explains our ‘Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy’.

The circular economy is a term that has gained a great deal of popularity among both businesses and governments over the last few years. With its growth in usage, the number of ways in which the term is defined have proliferated. Although some consensus is developing among the different players working in the field, there remains a lack of clarity about what “circular” actually means in practice.

Many groups define the circular economy in terms of the types of activities and concepts associated with it: the use of new business models like leasing, collaboration across supply chains, using waste as a resource, etc. However, these types of characterizations ultimately don’t tell us what the circular economy actually is, because they don’t describe the end state: what will the world look like when it is “circular”?

Without answering this fundamental question, we lack a common understanding of what we’re trying to achieve, which makes it impossible to measure progress in any meaningful way. If we’re designing a product, for example, and have only limited resources to either invest in more expensive, certified, renewable materials; or in the up-front costs needed to set up a product-leasing scheme, which will produce the more circular result? If we take the activity-based definitions of a circular economy, which suggest that making use of any of these practices makes something circular, then we don’t get much insight on what choice to make. And in fact, we know that simply choosing renewable materials does not always result in less environmental impact or greater value delivery – nor does adopting a leasing scheme.

Defining the Circular Economy

Over our years of advisory and development work in the field of the circular economy, we at Metabolic have frequently run into the issue of needing to handle trade-offs in circular design and decision-making, or needing to quantify progress towards circular goals. For this reason, it became essential for us to define the performance characteristics of a fully circular economy.

A great deal of focus in the circular economy field is on the management of materials and ensuring that resource cycles are closed, in a similar way that occurs in natural ecosystems, where water and nutrients are continuously cycled. So we began by taking this principle to its ultimate conclusion: in a circular economy, all materials should be used in such a way that they can be cycled indefinitely, just as they theoretically can in nature.

This statement, however, implies some additional complexities: we don’t just want these materials to be theoretically possible to recover – it has to happen on a time-scale that’s relevant to people. For example if we create wastes that need thousands of years for recovery – which is potentially the case with nuclear waste – this doesn’t exactly address our original goals or criteria.

Aside from this timescale issue, there’s an important recurring principle within discussions of the circular economy, and that is around the preservation of value and complexity: we want to ensure that materials can be cycled at the highest value possible, preferably as whole products, then as components, and finally recycled back down to basic raw materials (which can be extremely energy-intensive). Even this cascade is oversimplified here, and can look quite different depending on the context. For example, with a very energy-inefficient product such an old refrigerator, it may actually be systemically better in terms of energy impact to just scrap it and replace it with a newer model than to extend the life of the whole product. But the general principle of preserving complexity is clear.

Thinking through how materials should ideally be handled in a circular economy leads to all kinds of further conclusions regarding material toxicity, the scarcity of certain materials, the persistence of certain materials in the environment, and many other parameters. On this basis, we have developed a set of circularity factors that provide guidelines for the optimal use of materials for different functions. These are metrics that we use to define a material based on its properties such as recyclability, scarcity, toxicity, etc. Using these factors, we have developed shorthand recommendations for how certain materials should be used to uphold circular economy objectives.

Beyond Materials

In undertaking this exercise, we immediately realized that once you start developing goals for how materials should ideally be managed, you also run into many adjacent issues. Materials are just one type of resource in our economy, where all flows are ultimately connected and influence one another. In a world with infinite and free energy, it’s very easy to design and develop systems that will fully recover all materials through extremely costly and energy-intensive recycling processes – which is how we currently recover metals from electronic waste, for example.

However, because energy is also a constraint in our current system (even renewable energy is generated by devices that are made of scarce materials) and often comes with high levels of environmental impact (such as CO2 emissions), we also need to treat it as a scarce resource that should ideally be conserved. Ultimately, in a circular economy, all energy should be supplied from renewable or otherwise sustainable forms – like geothermal, which is not technically renewable, but we consider it a sustainable resource.

To achieve this, the efficiency of our energy use also needs to increase significantly. Although we know the total amount of energy available on the planet is not a constraint as the sun produces more than enough for everything we need, collecting this energy in usable form does require the use of scarce materials, which are a constraint themselves.

As we continue to explore the implications of striving for a fully closed, circular material cycle as a cornerstone of the economy, we ultimately encounter many other connections throughout the economic system that need to be arranged in a way which upholds broader human ideals. In the end, this exercise resulted in a set of seven characteristics which describe the end state of the circular economy once it has been genuinely achieved. These are idealized features that may never be possible to achieve, but they provide a specific set of targets we can aim for. Furthermore, each one can be characterized in greater, quantitative detail, forming the basis for Circularity Indicators, or KPIs, in many different contexts.

The Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy

- Materials are cycled at continuous high value. Material complexity is conserved by cascading materials in their most complex form for as long as possible. Material cycles are designed to be of appropriate lengths for human time scales and the natural cycles to which they are connected. Scarce materials are preferentially cycled at shorter intervals so they can be recovered sooner for reuse. Materials are transported within as small a geographic range as possible. Materials are not mixed in ways which preclude separation and recovery, unless they can continue to cycle infinitely at high value in their mixed form (although this is still not ideal because it limits choice). Materials are used only when necessary: there is an inherent preference for dematerialization of products and services.

- All energy is based on renewable sources. The materials required for energy generation and storage technologies are designed for recovery into the system. Energy is intelligently preserved and cascaded when lower values of energy are available for use, such as heat cascading. Density of energy consumption is matched to density of local energy availability to avoid structural energetic losses in transport. Conversion between energy types is avoided, as is transportation. The system is designed for maximum energy efficiency without compromising performance and service output of the system.

- Biodiversity is supported and enhanced through human activity. As one of the core principles of acting within a circular economy is to preserve complexity, preserving biodiversity is a top priority. Habitats, especially rare habitats, are not to be encroached upon or structurally damaged through human activities. Preservation of ecological diversity is one of the core sources of resilience for the biosphere. Material and energetic losses are tolerated for the sake of preservation of biodiversity; it is a much higher priority.

- Human society and culture are preserved. As another form of complexity and diversity (and therefore resilience), human cultures and social cohesion are extremely important to maintain. In a circular economy, processes and organizations make use of appropriate governance and management models, and ensure they reflect the needs of affected stakeholders. Activities that structurally undermine the well-being or existence of unique human cultures are avoided even at high cost.

- The health and wellbeing of humans and other species are structurally supported. Toxic and hazardous substances are minimized and kept in highly controlled cycles, and should ultimately be eliminated entirely. Economic activities never threaten human health or well-being in a circular economy. For example, successfully recycling e-waste by having people burn it over open fires is not considered a “circular” activity despite the fact that it results in material recovery.

- Human activities maximize generation of societal value. Materials and energy are not currently available in infinite measure, so their use should meaningfully contribute to the creation of societal value. Forms of value beyond financial include: aesthetic, emotional, ecological, etc. These cannot be brought down to a common measure without making gross approximations or imposing subjective value judgements; they are, therefore, recognized as value categories in their own right. The choice to use resources maximizes value generation across as many categories as possible rather than simply maximizing financial returns.

- Water resources are extracted and cycled sustainably. Water is one of our most important shared resources: sufficient quantity and quality of water is essential to our economy and our survival. In a circular economy the value of water is maintained, cycling it for indefinite reuse while simultaneously recovering valuable resources from it whenever possible. Water systems and technologies minimize freshwater usage, and maximize energy and nutrient recovery from wastewater. Watershed protection is prioritized, and harmful emissions to aquatic ecosystems are avoided as a top priority.

Emergent properties

You might notice that surrounding our Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy we have three emergent properties: equity, transparency, and resilience. These relate to how a circular solution connects to the world around it. If we’re designing a circular, sustainable model, we also have to pay attention not just to how we’re designing the individual elements, but to how those elements are linked to one another. For example, you can develop a fully recyclable cell phone that meets the criteria of the seven pillars. But for it to be really circular, we want to make sure that it is:

- Equitable – designed with principles of equity in mind, so it can, for instance, be affordable enough to actually be distributed throughout the system.

- Transparent – so you can track and trace the materials, and understand what is in the product.

- Resilient – making sure that there is a lot of knowledge transmission around how it works, and how it is supposed to be disassembled.

Prioritization and Weighting

An important note on the Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy is that in making decisions, not all of these outcomes should be equally prioritized. When we consider the state of the global system, there are some areas that are under extreme threat and close to key systemic “tipping points”. Though climate change is one of these areas, there are some that are even more severely impacted, like biodiversity loss. According to the WWF, monitored vertebrate species population abundance declined on average by 58 per cent between 1970 and 2012, and we are at risk of reaching irreversible tipping points in this area. For this reason, we suggest prioritizing certain types of impacts (and therefore indicators) over others, which is something we also recommend in indicator selection processes.

Some of the impacts that need to be prioritized over others include:

- Long-term, irreversible impacts

- Impacts which undermine the ability of the earth to provide a safe operating space for humans

- Impacts for which the outcomes for people or the environment have a high degree of uncertainty

Taking all of these emerging insights together, we have formulated our own working definition of the circular economy:

The circular economy is a new economic model for addressing human needs and fairly distributing resources without undermining the functioning of the biosphere or crossing any planetary boundaries.

Metabolic CEO Eva Gladek presenting the Circular Rotterdam proposal, a municipal strategy developed around the seven pillars of a circular economy.

Using the Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy

With these clear performance outcomes in mind, the process of natural selection, so to speak, will support the evolution of economic rules and incentive structures that actually achieve these end results. Technologies and business models that support not just one, but all seven of these goals, will be the ones that rise to the top as the most successful. So, we don’t arbitrarily support “product-as-a-service” models because they have been associated with the circular economy; rather we look at where, and under which conditions, these models actually result in better circular performance across the board.

For us at Metabolic, these seven pillars of the circular economy are an essential tool. With it, we are able to make sure that we’re approaching problems in a systemic manner. Whenever we recommend a course of action as part of a circular strategy, we make sure to evaluate whether or not our proposed solution for one area of impact will not be causing a problem or externality in one of the other target areas of performance. This problem, called “burden shifting,” occurs commonly when you’re focused exclusively on one problem (for example: making light bulbs more energy efficient), without noticing that your solution could have negative, unintended consequences (your newly efficient light bulbs require the use of toxic and hazardous materials).

Perhaps even more importantly, as we have refined these seven pillars over the years we have been able to translate them into quantitative tools – metrics and indicators – that we can use for evaluating the circularity of products, projects, businesses, and investment portfolios. For instance, we’ve developed a set of indicators for the Municipality of Amsterdam in order to assess the circularity of new building projects. Using this tool, City officials will be able to determine which of the proposed projects during a tender process should be selected for development, thus keeping Amsterdam’s urban development on a circular path.

Refining and collaborating

We’ve developed these Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy through a trial and error process over the course of hundreds of projects. For us, they offer clear signposts for how to make genuine strides towards a circular economy. We invite everyone working in the circular economy field to make use of this framework and the tools we have developed around it. We see it as a complementary resource to the lists of business models and circular economy approaches that are already more broadly in use. But as practitioners, we continuously refine our ideas as we run into new situations and are faced with new trade-offs.

We will continue to build on the Seven Pillars of the Circular Economy and we welcome other relevant experts and advisers to join us in this process. If you have thoughts or comments that immediately spring to mind – or other ideas for how to make use of this framework – please reach out to us. We’d love to start a conversation.