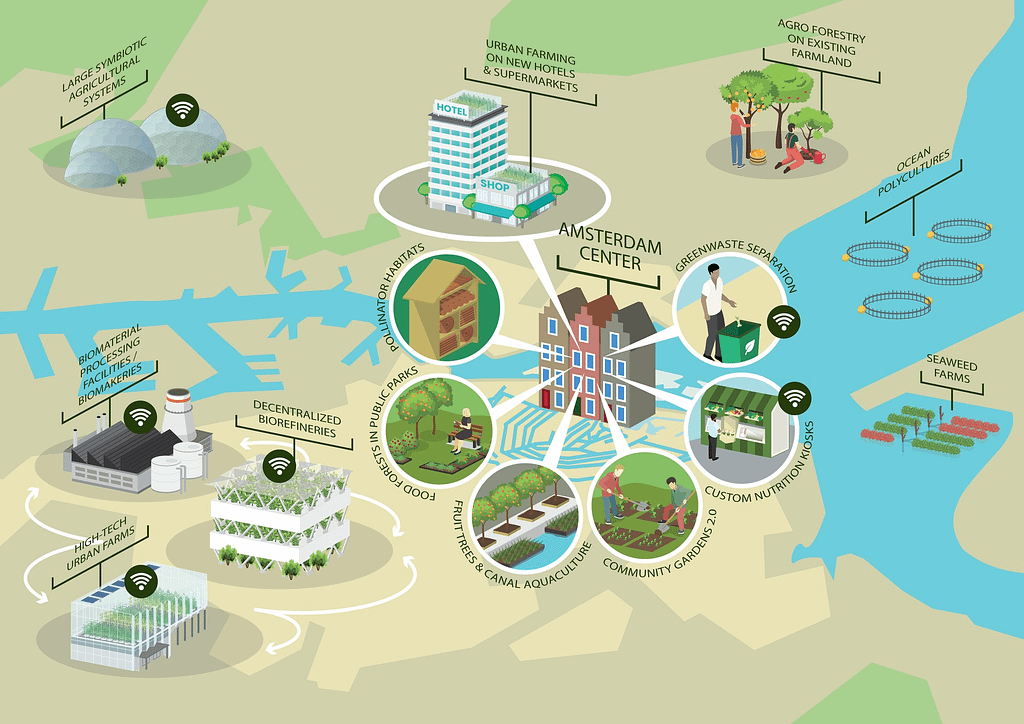

Chris Monaghan travelled to 2050 to see how a circular urban food model and smart agricultural production can provide food security for Amsterdam’s citizens.

It’s a society where young people are motivated to become farmers, knowledge is shared and organizations are driven by sustainability and people – and not by profit. There’s a BioMakery, a restaurant that prints the meal of your dreams (without the carbon footprint of your nightmares), and Amsterdam’s world famous Green Light District. Here’s an edited version of Chris’ vision that was a semi-finalist in the Food System Vision Prize.

I press “print”. There’s a whirr, a whoosh, some clicks and a clatter as a printer above kicks into action. Within moments, creamy lobster bisque emerges from the printer’s nozzle into a bowl in front of me. I gulp down a mouthful. It’s just as I remember it when I was growing up in New England.

My son David scans the ingredients, flavor and nutrition profiles and once he has chosen his meal of choice – a paella he loved when we were in Barcelona – he too presses “print”. We’re at the 3D’licious Cafe, the restaurant at Amsterdam’s Urban BioMakery, where you can create almost any flavor profile, and everything is entirely plant-based and made on site.

It’s David’s 16th birthday; we have come to the BioMakery on his birthday every year since he turned 10 on 2 July 2044 – that was the day it opened its doors for public tours. I figured it was a great place to take him for his birthday because he has an insatiable appetite for science and technology. I was right. From that day, he wanted to be a food system engineer, a profession now equal in status to that of a doctor.

Every year, David spends his birthday traversing the nooks and crannies of Amsterdam’s globally renowned food system, which embodies the immense progress we’ve made in building a sustainable society. Now, on his 16th birthday, we’re back and we’ve made our way to the 3D’licious Cafe, which is always our first stop before heading off on our annual tour to see how the BioMakery has evolved over the years.

The BioMakery, which took three years to build and another two to finetune, was something the region had been building towards for more than two decades. It’s a giant vertical urban farm attached to a bioprocessing center, churning out food, feed, and fiber. It’s an impressive mix of science and tech, built for the public’s benefit, and represents a new era of economic thinking.

The crown jewel of Amsterdam’s food system is its agro-ecology knowledge hub, which serves as the brain of the regional farming system. The center, which locals call FarmLab, launched in 2024 to explore advanced ecological approaches to aquatic and soil-based farming methods. It’s a mosaic landscape of agricultural land and nature, a mix of water, trees, pastures, and cultural elements. The sky buzzes with insects and rings with the songs of dozens of bird species. Biodiversity has made a comeback here over the previous decades. Whereas insect and bird populations were under great pressure when I was young, some threatened species like sparrows are now flourishing.

When I was young, few people wanted to be farmers, but that changed. Technological advances have made farming easier and progressive land policies have helped young people get access to land. On many farms, robots do most of the harvesting and planting, while the farmer is more of an ecosystem engineer and data manager — like a conductor of an orchestra where soil and plant health is the music.

Marije, our tour guide, takes us on a walkthrough of the center, starting with the main soil-based plots. One system consists of free-range chickens walking among a multi-strata system with layers of herbs, shrubs, and trees. Apple trees grow fruits, alder trees fertilize the soil with nitrogen, willow trees form protective wind shields, while walnut trees provide a valuable crop. The chickens, by eating insects from the topsoil, fallen rotten fruits and weeds, keep the orchard clean of pests and diseases, and through their droppings simultaneously fertilize the orchard, returning essential nutrients like phosphorus. A balanced mix of cover crops is sown to suppress undesired weeds and serve as nutritious chicken feed.

Our next stop is the aquatic ecology lab. We walk along the water to the large, semi-open greenhouse that straddles the canal, with a tall square archway cut through the center to allow ships to pass through. Square pens line the canal. Robotic arms, which move on rails that form a lattice structure above the overpass, are designed to lift up cages with a cylindrical structure in the middle. The structure provides the necessary growing environments for algae, oysters, clams, and mussels. Two pens at each end contain fish, which create a symbiotic aquaculture system alongside the plants and crustaceans. Marije shows us an extraction in progress, where the arm lifts a cage out of the water for harvesting and testing.

We return to the center of the FarmLab and to a handful of two-story buildings, which are small-scale factories that serve as the processing and distribution hub of FarmLab. The goal is to improve upon on-farm processing and distribution by making it affordable and efficient to own or share such a facility. In one of the buildings, walnuts, hazelnuts, perennial legumes, fruits, vegetables and mushrooms are processed and packaged. The facilities also pre-process harvested crops like wood, seaweed, and reeds produced at FarmLab that are destined for further processing into building materials, fuel, animal feed, and micronutrients for food fortification.

In another building, workers fill electrified cargo bikes that take fresh and processed food products, and non-food products, all over the region. Small automated platforms filled with goods zip around, bringing full pallets to workers who scan and load them onto cargo bikes. The bikes are charged wirelessly while they sit idle, and can be switched to auto-pilot mode, allowing the rider to relax.

Our last stop is the control room: FarmLab’s nerve center. A wall of monitors show real-time flows of data that help the FarmLab make optimizations and keep close track of its ongoing research. Marije tells us about self-driving chicken coops that move chickens throughout the orchards, using real time data to pinpoint where to locate itself based on the demands of pest and disease control as well as nutrient availability. After harvests, data informs farmers and their robot assistants which plants should follow in order to mimic ecological succession and boost soil health.

The next stop on our tour is Amsterdam’s Urban BioMakery, which is in one of the city’s coolest mixed-use developments. In the front is a pair of large domed greenhouses, that serve as a publicly accessible indoor arboretum. Walls of water and greenery line the entryway and the corridor brings us to a central area where a public display explains how the facility serves the local population. Holographic images show how materials, water, energy, and nutrients flow inside the building and around the city. A table layered with augmented reality describes the history of the Amsterdam food system and this facility. Another interface allows visitors to prioritize different outputs to see how they can create balanced and synergistic systems of their own.

We enter a glass box that moves along a track throughout the facility so visitors can see the inner workings of the BioMakery. We travel through a tunnel, which reveals details of the history of the facility:

“The facility started when a digital simulation was developed to model how this facility might function, allowing scientists, engineers, systems architects, and policymakers to understand the implications of different scales, technologies, policies, and collaborations working in tandem. Hundreds of thousands of variations of the BioMakery were simulated to find optimal sizes and combinations of processes, as well as to understand dependencies, risks, technological gaps, and business cases. Improvements in biorefinery technology led to this facility being commissioned in 2038…”

Our vehicle enters a room the size of a football field. It takes my breath away. It’s the main plant production zone. We are surrounded by towering columns of leafy greens, herbs, peppers, berries, and gastronomic wildflowers. Robots zip around to harvest trays of mature plants to be cleaned and processed and leave trays of readied seedlings in their place. Above us is a large glass ceiling, mixing natural and artificial light.

Our automated guide announces that we’re entering the mycology zone, where mushrooms and mycelium are produced in darkness. Workers in “bunny suits”, wearing special glasses that project soft light in front of them, move on mechanical platforms harvesting mushrooms in one area and placing newly prepared substrate in another. Light appears again as our vehicle enters the bioprocessing hub. Sun shines through the greenhouse overhead onto big green algae bioreactors that create nutrient-dense inputs for food printing. Spent mushroom substrate is taken to large heaters to be turned into biochar, which is sent on to soil-based farms around the region. The process of decomposing the substrate into condensed form is called pyrolysis, and can be a major booster to soil health.

Our vehicle approaches biorefineries that can extract biochemicals, biogas, bioethanol, and compost, all from the same material. Finally, we arrive at the distribution hub. People work with robotic assistance, conducting quality control and packaging finished products for shipment.

Crates from compressed mushroom fibers are stacked on conveyor belts, placed on boats and transported around the country. Other crates are loaded onto electrified cargo bikes for last-mile delivery.

The BioMakery is co-owned by regional utilities, the government, its suppliers and its customers, and often collaborates with NASA and the European Space Agency to develop innovations to make food production and processing even more efficient. Knowledge generated at the BioMakery is available to not-for-profit organizations without charge and commercial organizations can license any of the knowledge cheaply. The goal is to ensure the BioMakery is in the public interest. Thanks to this approach, hundreds of similar facilities have spawned around the globe. The demand for advice, support, and research collaborations has been so significant that the BioMakery has created a dedicated team to work to support other initiatives springing up around the world.

We hop on bikes and cycle to the Green Light District in Amsterdam North. The city built a mixed-use neighborhood in the 2030s to pioneer the circular economy and facilitate innovation in agriculture, buildings, water, and energy. The name is a tongue-in-cheek play on Amsterdam’s Red Light District, and was meant as a signal that the city had entered a new chapter for what it wanted to mean to the Netherlands. The Green Light District is like a town within a city; there’s a six-story standard for the height of the buildings and every rooftop is devoted to public space or horticulture. Providing more public space for recreation above allows the neighborhood to prioritize essential services at ground level. David and I visit the Green Light Bazaar, which buzzes with small grocers, brewers, cafes, textile makers, and repair kiosks. Here, reverse vending machines provide interesting products and services in return for e-waste, food waste, or other materials. Visitors can use augmented reality to explore all the food initiatives at the Open Food Lab. There’s also a food-and-farming helpdesk, where urban residents and peri-urban farmers receive information and support about resources.

We stumble into the Agtech Venture Hub, home to about 50 small startups, an advanced makerspace and biolab for prototyping, a big co-working space anyone can sign up for, and a theater for presentations and events. The Agtech Hub only accepts steward-owned, mission-driven startups. In return, the startups receive cheap rents and access to a variety of resources. Even here, at the mecca of startup enterprises inside this innovative tech district, the tide has turned against the concept of profit being a respectable organization’s primary goal. It’s a lively place with passionate people working with the frenetic energy of ER doctors.

Across the walkway from the Agtech Hub is the Green Light District community farm. The workers here are calm; a stark contrast to the Agtech Hub. Large hedges line the perimeter of the farm, creating a green-walled oasis of tranquility that feels like a refuge from the crazy bustle of urban life.

David and I take the train home. His nose is buried in his notebook where he jotted down his observations from the day’s adventure. Our grandparents left a legacy of inaction on climate policy. We have had to deal with the consequences but with initiatives like biomakeries and so many committed and innovative young people like David determined to make a real and lasting positive impact on the environment and solve complex world problems, Earth is in good hands.