Metabolic joined the webinar ‘Denver, Boulder and Beyond’ during Circular Cities Week, designed to explore the meaning of a circular city, how we can move towards closing as many loops as possible, and what major challenges lie ahead as we attempt to implement the circular economy concept.

Our cities consultant Andrew McCue contributed to a panel hosted by Paul Hutton from Cuningham Group Architecture, Jamie Harkins, Sustainability Coordinator for the City of Boulder, Susan Renaud from Denver City’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resiliency (CASR), and Kåre Poulsgaard, head of innovation at GXN Copenhagen.

- CEC Circular Cities Week 2020: DENVER, BOULDER & BEYOND

A circular city goes beyond materials cycling

“At the city scale, [the circular economy] can apply to everything that we do, from our materials management to procurement, land-use, food systems, infrastructure, buildings, transportation systems, policies. You name it, we need to start looking at how we can integrate this kind of thinking into everything,”

– Susan Renaud of the Denver CASR Office.

There are multiple definitions for the circular economy and how it applies to the urban environment. While materials cycling is one piece of the puzzle, the view adopted by panelists was much broader. For Jamie Harken who leads Boulder’s circular economy initiatives, a circular city is not only one that aims to eliminate waste and keep materials circulating as long as possible, but ultimately integrates other city systems such as energy and wastewater into circular practices.

Building on this, Andrew McCue spoke about the Seven Pillars of a Circular Economy – a concept widely used here at Metabolic – which views a circular economy as more than material and product cycling, including concepts such as ecological threshold, social health and wellbeing, and inclusion and equity. According to Andrew, a circular city should promote connectivity, inclusion, resilience and community, primarily generating value in a variety of forms beyond financial (e.g aesthetic, health, social, etc) for its residents.

The importance of data and monitoring

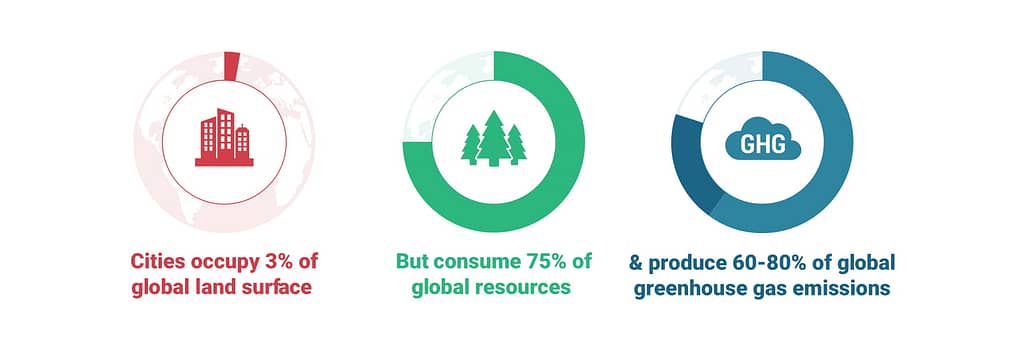

Cities and regions are widely considered to be key levers for moving from linear systems to circular ones. The reason for this is that although cities represent only 3 percent of the global land surface, they consume 75 percent of global resources and are responsible for 60 to 80 percent of global greenhouse emissions through the materials and energy they consume.

Citing their collective work on the Circular Boulder Report, Harken and McCue shared insights on one way to kickstart a city’s circularity journey: conducting an urban metabolism study. Usually, this is done through a material flow analysis, which, according to McCue is, an overview of “materials coming into” and “waste and emissions coming out of the city”. Once those are identified they can be categorized by commercial and residential sectors, material types, diversion rates and most importantly which materials have a disproportionate economic or environmental impact.

McCue mentioned that continuous monitoring is a critical enabler and guide for achieving a circular economy rather than an initial step. He shared the example of Rotterdam:

They’re now moving towards having a circular construction sector in the city. And they’re moving from individual snapshots of data into year over year monitoring of material consumption.”

Urban mining is about viewing the built environment as a valuable resource. Buildings are a host for materials and products which, at the end of their lives, usually end up as waste. The key here is to make sure the materials coming out can circulate at the highest value possible. We can do this by having a reference to what is in each building, with, for example, a material passport for each building, showing every material that has gone into the building and how it is being used. The materials passport can serve as a tool to estimate their value and to figure out how to extract them.

Circular solutions

When looking for solutions to create a circular city, circular products or buildings, we tend to look at national legislation. We know that 12% of the global GDP is controlled by public procurement and the government can help to create market demand. One simple starting point could be developing standards which cities can refer to and apply.

McCue shared an example of how a region can apply circular thinking to its procurement process: Manitoba, a Canadian province. With the Winnipeg Metropolitan Region, Manitoba implemented a joint procurement enterprise separate from municipalities. This method helps municipalities gain a procurement intermediary without taking on the responsibility themselves, therefore enabling them to jump ahead in their circular economy projects at a regional and national level. Cities can align their procurement standards and priorities, purchase in bulk, and share/reduce the burden of administration. This kind of setup is also a great foundation for future product and material sharing or reuse. Cities have control over procurement and, to a lesser extent, over their waste streams, however, they can only access truly ambitious circular economy solutions in these areas at larger scales. This joint procurement enterprise is a shortcut to catapult their projects to the next level.

“To develop a circular economy, you have to set the economic framework, the mindset, the worldview, that materials should be treasured, and it’s not about infinite consumption and growth. Then, adjust tax policies and regulations and incentives and subsidies at the regional and national level, and then trade agreements at the international level. That will start to affect the biggest material consumers and emitters in the world.“

– Andrew McCue, Cities Consultant at Metabolic

Urban agriculture is a crucial issue when looking at a circular city project. Metabolic has worked with cities to find circular solutions to this problem. Harken mentioned that the report Metabolic worked on for Boulder has helped to illuminate key issues in the food (waste) system in the city, and through that, they have started implementing educational efforts as a starting point. Denver’s food systems department has also been working on food waste, food resiliency planning and recently, a partnership with a group named Zero Foodprint; a non-profit which created a structure in which restaurants can add a 1% opt-out surcharge to their bills which will then fund regenerative agriculture projects in the region.

Circular by design

Towards the end of the webinar, panelists were asked to answer some of the audience’s questions. One issue raised was the topic of recycling solar panels. As McCue explained, a renewable energy transition cannot work without a circular economy. To create a circular pipeline for solar panels and wind turbines, they need to be designed for disassembly from the start. Metabolic published two reports on critical metal demands for renewable energy production, one concerning the broader energy transition and the other relating electric vehicle production. Unfortunately, the takeaway from these reports is that, with our current consumption rate, we risk future supply issues for specific critical metals. Thus, design processes need to continually be updated to be less material-intensive while being aware of the scarcity of the materials used. Electronics are nowadays being collected to recuperate some of these materials. However, this would need to be done on a larger scale and is a labour and cost-intensive activity.

Looking at the built environment more broadly, the head of innovation and their team at GXN recounted participation in a program named ‘Circuit’ – where the cities of Copenhagen, Hamburg, Helsinki, and London focused on how to build flexibility into the built environment. Local architects, engineers and suppliers built 12 demonstrations in each city working with local value chains. Sharing knowledge and tools between cities and acting on the shared issues is the main goal of these projects.

“If we can design the built environment so it’s more flexible, we will resist tearing down buildings, and we can increase the value of the materials we put into them”

– Kåre Poulsgaard, head of innovation at GXN Copenhagen.

Andrew McCue went on to discuss two similar projects Metabolic helped design and build in Amsterdam: De Ceuvel and Schoonschip. The goal for De Ceuvel was to turn a dilapidated polluted shipyard into a community-led, sustainable and circular neighborhood centre. The old houseboats used to build De Ceuvel serve as offices for sustainable entrepreneurs, a popular cafe and a greenhouse. The tenants trade energy credits from their solar panels with each other. With credits generated from the rooftop, residents can pay for a beverage. They used techniques such as water sharing between houseboats and these pilot ideas were valued by the city. Moreover, vacant city-owned land was made available to the community via a contest, McCue explains. This community wanted to build a sustainable space together. It has since become a major staple in the neighborhood all the while continuing to experiment with circular economy technologies and techniques.